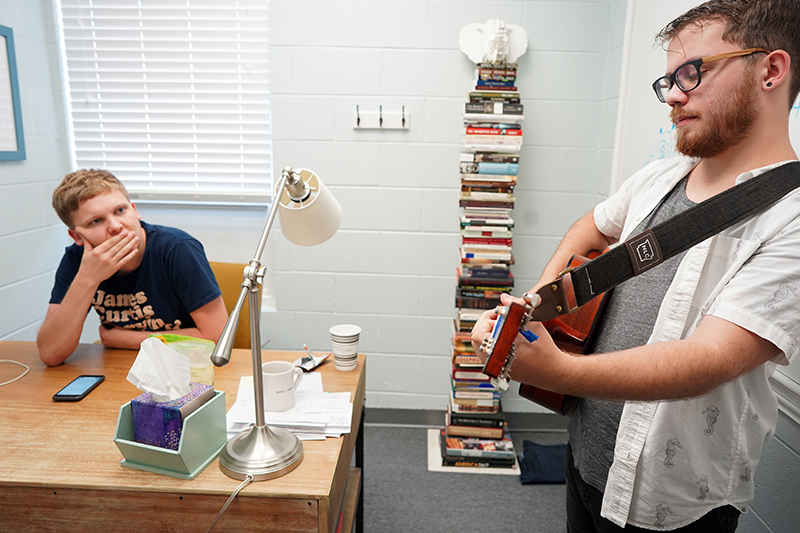

In a closet-size office at the rear of a squat brick building in Richmond, Virginia, four young musicians have sequestered themselves, intent on putting the finishing touches on a worship song several weeks in the making.

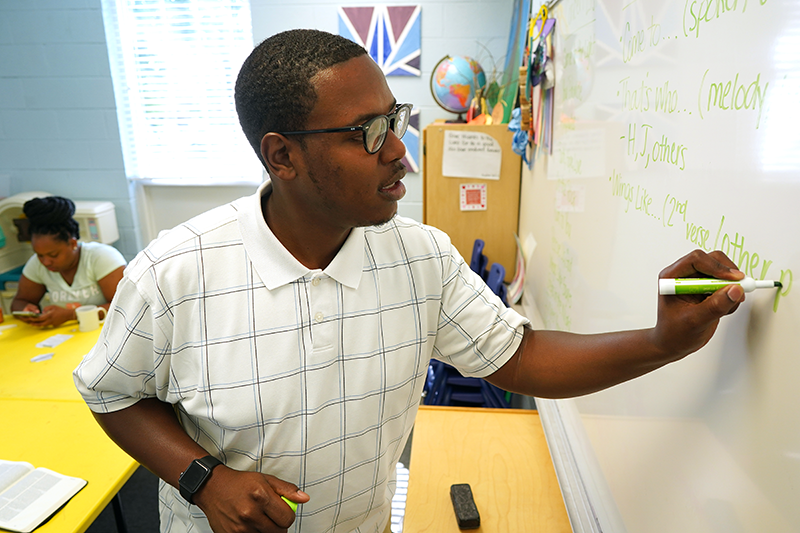

Now it’s crunch time. In roughly two weeks, the group -- participants in the Urban Doxology Songwriting Internship -- will perform more than a dozen original works while leading worship services at a nearby multicultural congregation. For more than an hour, they tweak the melody and fiddle with the lyrics of “That’s Who You Are,” a song celebrating the unconditional love of a God who never gives up on his very flawed children.

The sounds of humming, whistling and guitar strums are broken by brief silences until, eventually, things come together and the room erupts in high-fives and fist bumps.

“OK, I think we’ve got something,” one announces. Now, time to run it by the rest of the interns.

The Urban Doxology summer internship is a leadership development program in which young musicians study theology and collaborate on what sponsors call “the soundtrack of reconciliation.” Specifically, they produce worship songs that speak to the challenges of Church Hill, the racially and economically diverse Richmond neighborhood where the interns live throughout the eight-week program.

Over the last eight years, nearly 50 young musicians of varying racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds have been through the songwriting internship, creating dozens of songs acknowledging the world’s brokenness and God’s infinite power to repair and restore.

Creating theologically sound worship music that reflects the shared experiences of a diverse community isn’t easy. Like reconciliation itself, it requires working collaboratively, day after day, to tear down that which divides and replace it with a culture of understanding and love.

It’s no coincidence that the internship works much the same way.

‘A metaphor for life’

“Songwriting is a metaphor for life,” said David Bailey, a musician and former worship pastor who founded the internship in 2011 through his Richmond-based nonprofit, Arrabon. “The process of what we’re doing can and should be used everywhere.”

How might songwriting and reconciliation also be metaphors for church?

Bailey, who is black, grew up in a largely white Richmond suburb but worshipped with his parents each Sunday at predominantly black urban congregations. A pianist and saxophonist, he put himself through Virginia Commonwealth University by playing gigs on weekends -- often, a country club Friday night, a jazz club Saturday evening, a white suburban church Sunday morning and an inner-city Pentecostal service Sunday afternoon.

“I’m real comfortable with ‘the other,’ however that’s categorized,” said Bailey, who lives with his wife, Joy, in the Church Hill neighborhood, an economically depressed community where Arrabon and the internship are based.

The program’s roots extend back to the early 2000s, when several Christians, mostly white, began moving into Church Hill from the suburbs, hoping to promote racial reconciliation and community development in one of Richmond’s tougher neighborhoods. They established a faith-based preschool and high school, tutoring services, life-skills and job training, and leadership programs for youth. But the newcomers and longtime residents weren’t worshipping together until the Rev. John Perkins, a noted civil rights activist, urged them to do so during a visit to the area.

With Perkins’ encouragement, Church Hill residents established East End Fellowship, a multiethnic, economically diverse congregation focused on reconciliation. As East End’s first worship pastor, Bailey was one of the church’s few leaders of color, but he worried that no leadership pipeline existed to attract more.

How specifically does your church’s worship reflect its life together and the life of the surrounding neighborhood?

In 2008, he founded Arrabon -- from a Greek word meaning “a foretaste of what is to come” -- to provide resources and training for other churches wanting to worship in ways that reflect the diversity of their communities. Three years later, Arrabon launched the Urban Doxology Songwriting Internship as a ministry to empower young Christians -- primarily those of color -- to lead reconciliation efforts in their own communities.

Recognized in 2016 by Christianity Today as one of the “most creative Christians we know,” Bailey travels roughly 100,000 miles a year, speaking about the church and social justice and helping equip communities to honor multiculturalism in worship. As a result, he’s gradually withdrawn from the internship’s day-to-day operations, turning virtually all responsibility over to program alumni. It’s a model of “discipleship through apprenticeship,” Bailey said, that gets better and better as he relinquishes the reins.

‘Disciples making disciples’

“Success for me is that, at any given time, we have multiple generations of people who came through this program mentoring and discipling others to keep it going,” Bailey said. “We have disciples making disciples.”

How does your church prepare young people for leadership? Where is it relinquishing the reins?

Elena Aronson, a former intern who now directs the program, estimated that about a third of previous interns have remained in the community; most, whether in Richmond or elsewhere, are in ministry or mission work.

Aronson was the only white intern in the inaugural group of five in the summer of 2011. Though musically proficient, she didn’t consider herself a songwriter and worried whether she’d be able to contribute meaningfully.

“I came out realizing there were things I could be involved with that I didn’t have to be an expert at -- that I needed other people, and there’s beauty in that, the importance of dependency,” said Aronson, who lives in Church Hill. “There was a lot of soul work that went on.”

Like the internship, the application process is intense. Applicants must submit video and audio recordings and information about their musical backgrounds, faith journeys and cross-cultural experiences, and an original song based on Isaiah 58, which speaks to the importance of seeking justice in worship. Interns, generally ages 18 to 24, are chosen based on “character, competency and chemistry,” Bailey said, with preference given to minorities and Church Hill residents already involved in community reconciliation efforts.

The result is a racially and ethnically diverse band of Christians from various denominational and musical backgrounds who are commissioned to write worship songs that speak to the trials of the Church Hill community. The seven interns this summer, four black and three white, were from as far away as Wichita, Kansas, and Little Rock, Arkansas, and as near as 40 miles from Church Hill.

Each day, the interns attended lectures on race, class, and culture, learned about various worship practices, and studied Scripture together, focusing on themes of justice and reconciliation. In the music writing sessions, previous interns coached the newbies, challenging them to think critically about message, be honest theologically, and step out of their comfort zones musically and lyrically.

Because song lyrics can resonate with -- and stay with -- a worshipper more than the words of a sermon, the interns learned to make sure their songs don’t just sound nice but also reflect Scripture.

“It’s not about always singing the best song ever or the most recent song,” said vocalist Isiah Rankin, 22, of Memphis. “You can listen to music and it’s beautiful, but some lyrics are empty; they’re not really saying much. You want to sing lyrics that are theologically sound and are leading people to the truth of God so God can reveal himself.”

Broader internship

Although the songwriting and theological studies take place at the Arrabon offices, the internship extends far beyond the building. Every day, the interns are immersed in Church Hill and Richmond, the “Capital of the Confederacy” and a city with a long history of racial division. They live with host families in Church Hill, a few miles away from Monument Avenue, the historic and controversial boulevard dotted with statues of Robert E. Lee and other prominent Confederates. On their first day, this year’s interns took a bike tour through Richmond, including a stop near what was once one of the largest slave-trading sites on the East Coast.

East End Fellowship, the church where the interns pray and lead worship throughout the summer, meets across the street from Arrabon in the historic Robinson Theater, built in 1937 for the black community in Church Hill and named for Richmond native Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Although new homes have sprung up in recent years, the area is mostly made up of older homes, half-empty strip malls and government housing complexes.

What are the most pressing issues and challenges for people living within two miles of your church?

Understanding local context is essential if churches are to love and serve their neighbors, Bailey said. Yet many congregations don’t take the time to know the struggles of the people in the surrounding neighborhood. Being a reconciling church, he said, requires more than not being “proactively racist.”

“The question you’ve got to ask yourself is, ‘What am I doing to be proactively reconciling?’” he said. “Every society has some brokenness, and the church is supposed to be a healing agent.”

Where and how is your church “proactively reconciling?”

For intern Ian Schwegal, 21, of New Kent County, Virginia, this summer was the first time he ever lived in a large city. All summer, he said, neighbors dropped by his host family’s house to borrow paprika, for example, or ask for help starting a lawn mower -- or just hang out. The door was always open.

It was a lifestyle marked by community, he said.

“The people there are so incredibly real,” said Schwegal, who is white. “It’s the most Christlike setting I’ve ever seen.”

At first, the interns were reluctant to be candid and share criticism with one another, said singer Hanna Watson, 19, of Wichita, Kansas. But living in Church Hill and attending East End, they saw people of different backgrounds worshipping together and forgiving one another. As they witnessed neighborhood residents being vulnerable, they learned to open up with each other as well.

“We realized vulnerability would be better for our relationships, better for our worship and better for the songs we were writing,” said Watson, who is black.

Writing the songs

To spark the songwriting, the interns were often given a one-word prompt, like “healing” or “justice,” or a verse from Scripture. Many of the 39 songs the group wrote this summer came from stories they shared with each other about personal struggles, questions of faith, feelings of inadequacy and anger at being judged.

“That’s what made our songs what they were,” said Alex Canady, 24, a black keyboardist and mechanical engineering student from Lansing, Michigan. “They came from the heart, from our experiences, from our trials and our truths.”

Whatever the source, the songs were well received by Church Hill residents. At the final performance on July 29, a crowd of 450 was on its feet in the Robinson Theater. The interns performed 14 worship songs, from hip-hop and rap to gospel and R&B, and talked about the impact that the program and Church Hill had made on them.

“I have never heard the voice of God as clearly as I have this summer,” Janae Durr, 24, of Chicago told the crowd.

Durr, who is black and working on a master’s degree in social work, said the community and East End Fellowship had welcomed the interns with a warmth and grace beyond anything she expected.

“It’s easier to be vulnerable at this church, because they have hearts willing to forgive,” she said. “There’s no way we can bring about reconciliation outside the church if we don’t bring about reconciliation inside the church first.”

In what ways is your church diverse? How reconciled is it internally?

In 2014, former interns created a band, Urban Doxology, to perform the music that is emerging from the summer program. The band, now working on its third album, helps raise money for the internship by performing at churches, conferences and youth events across the country, as well as an annual gala in Richmond. This summer, the band also taught songwriting to teens at the Center for Worship and the Arts at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, and performed afterward at nearby 16th Street Baptist Church.

Eric Mathis, the center’s director and an associate professor of music and worship at Samford, said the group is passing on the faith, but in an unexpected direction.

“We talk a lot about passing faith down to the next generation, but not enough about passing faith up from the younger generation,” he said. “Teens and young people have a faith that’s spirited and contagious, and older people of faith -- we need that passed up to us.”

But the willingness to empower young leaders is only part of what makes the internship distinctive, said John Witvliet, the director of the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and a professor of worship, theology, and congregational and ministry studies at Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The internship, he said, also pays close attention to local context and draws from it to create Scripture-based culture. The program deliberately helps the musicians cultivate relationships with each other and with the community they’re serving.

Deep relationships

“These interns don’t fly in for a weekend conference,” Witvliet said. “They spend the whole summer together, eating meals, debating and challenging each other, annoying each other and forgiving each other. There’s a depth of relational engagement.”

Those deep relationships were at the heart of former intern Makeda McCreary’s experience in 2016. Before that, McCreary, 26, always heeded her parents’ advice to steer clear of Church Hill. Raised in Richmond’s West End neighborhood, she grew up in a predominantly black church, where her parents were co-pastors. But in every other setting -- including her high school, with its Confederate soldier mascot -- she often felt like the only black person. When she left for college, she vowed that she’d make only black friends.

“I didn’t want to be in white spaces anymore,” said McCreary, who attended Shenandoah Conservatory in Winchester, Virginia, and Berklee College of Music in Boston before returning to Richmond.

During her internship, she lived with an older white couple in Church Hill, sharing a room and bunk bed with a white intern from Iowa whose brother was a police officer. The two became fast friends, bonding over faith, music and French press coffee. In early July that year, about halfway through the internship, two black men, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, were shot and killed within a day of each other by nonblack police officers (white and Latino, respectively) in Louisiana and Minnesota.

By then, McCreary and her roommate had built a strong relationship that allowed them to discuss the killings honestly. She wondered whether the white churchgoers at East End Fellowship would be as open to her rage and heartbreak as her roommate was. The following Sunday, when the pastor encouraged members to share their feelings, McCreary approached the microphone.

“I said, ‘I’m angry. I’m mad, and I don’t see where God is in this moment,’” McCreary recalled. “I said it there, and this community of white people, they embraced that. It quite literally restored my faith in white people.”

McCreary now lives in Church Hill, where she coaches the summer interns and performs in Urban Doxology. She is also music director at a nearby church that, although predominantly white, is embracing ethnically diverse worship practices.

“Being in the internship made me want to be a part of reconciliation,” she said. “People want church to be comfortable, but it’s hard. You just can’t have multiple cultures be in one space and be comfortable all the time. And that’s OK. We’re still family, allowing space for people to be ignorant and to grow. That’s the fullness of the kingdom of God.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Could songwriting -- and reconciliation -- be metaphors for church? How so?

- How specifically does your church’s worship reflect its life together and the life of the surrounding neighborhood?

- How does your church prepare young people for leadership? Where is it handing them the reins?

- What are the most pressing issues and challenges for people living within two miles of your church?

- Where and how is your church “proactively reconciling?”

- In what ways is your church diverse? How reconciled is it internally?