Editor's note: This article has been translated into Spanish.

When faced with an inability to pay their rent, mortgage or utilities, a situation confronting millions of American households in the wake of a pandemic, families or individuals are often asked to fill out lengthy forms to determine their eligibility for financial assistance.

The application process can be impersonal, even invasive. Applicants fill out details about household income and payment history and provide documentation of expenses, bills and previous payments.

However, residents in an inner-city neighborhood of Indianapolis completing similar paperwork for the nonprofit The Learning Tree come across at least a few probably unexpected differences. For one, the form consists of only a single page instead of three or four. And then two unusual questions at the end, under a section titled “Tell Me About You,” ask simply, “What are you good at?” and, “What brings you and your family joy?”

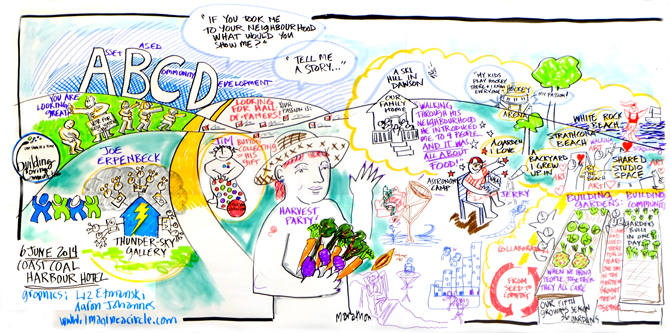

Those types of questions are at the heart of the mission of The Learning Tree, an organization that seeks to improve the quality of lives of people, communities, schools and businesses using a model called asset-based community development, or ABCD for short.

Instead of viewing low-income neighborhoods as areas that require outside help — handouts — to flourish, the team behind The Learning Tree seeks out ways to explore and tap into the gifts of residents to help support their neighbors in the Riverside, United Northwest and Clifton Place communities. All have a lower median household income than most neighborhoods in Indianapolis.

“There are people in neighborhoods, especially Black and brown neighborhoods, whose talents are untapped,” said De’Amon Harges, the creator of The Learning Tree and a resident of the area the organization serves.

“All of the people that are in our circle have a responsibility to be a witness of where God is working, particularly people in low-income places that are covered up — whose gifts and talents are unseen,” he said. “We need to find those gifts so they can be utilized in ways that build community, economy and mutual delight.”

Harges’ interactions with residents, primarily one-on-one conversations while walking through neighborhoods, regularly lead to projects. Gardeners provide produce for a community that is designated a food desert. Poets, storytellers and photographers document stories about their neighbors. Artists beautify the neighborhood with their work, and entrepreneurs mentor local youth.

The Learning Tree among 2021 winners

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners receive $10,000 to continue their work.

How do you provide opportunities to talk about what brings people joy?

Harges has been immersed in this type of neighborhood work for nearly 20 years, going back to when he was tapped to become a “roving listener” for Broadway United Methodist Church, an urban congregation in Indianapolis. Recognizing Harges’ gift for making connections and developing friendships, the Rev. Mike Mather asked him to go throughout the surrounding community to talk to people individually. The goal was to learn more about the gifts they had to share instead of focusing on their needs and what was wrong in the neighborhood, whether high crime rates, high vacancy rates or vandalism.

Indianapolis Deputy Mayor Jeff Bennett, who has been familiar with Harges’ work for more than 15 years, said the relationship-driven approach to community building has numerous advantages.

“There is more to community development than just dollars in, dollars out,” Bennett said. “As much, if not more, impact can be made at the human level through relationship building. So often at the government level, we can be so top-down. We devise and fund programs that we think communities want or need without listening to what a neighborhood says it could use in order to direct their own future.

“That’s where an organization like The Learning Tree excels so well,” Bennett said. “They can get to the heart of a neighborhood’s concern much more quickly and comprehensively than other organizations that do community development.”

Community building focused on relationships

Amanda Wolf, who oversees organizational and administrative work for The Learning Tree, often joins Harges and other Learning Tree partners as they walk through their neighborhood. During one of those walks in 2018, they started talking to several youth who were performing bike tricks.

“De’Amon asked them what they would like to see in their neighborhood and how they would like to spend their summers,” she said.

That particular conversation led to the development of a bike shop in Wolf’s garage, supported by 50 bikes donated by the Indianapolis Police Department. A neighbor with experience repairing bicycles trained the youth in how to fix, clean and sell the bikes.

“What I’ve learned over the years is that there really weren’t any needs except the need to be seen,” Wolf said. “Mainly what we’ve done through the years is shine light on the gifts that are already in our community, to let people know about them. The more we can do that, the better off our communities will be. We need to let everybody know what a diamond we have here.”

What are you doing to uncover gifts and talents in your community?

Other projects have emerged as a result of such conversations — repurposing discarded doors into works of art, covering boarded-up homes with enlarged photographs of residents, engaging in a neighborhood beautification project.

Harges noted that the beautification project was a great example of challenging the way city officials and organizations typically think about helping impoverished neighborhoods.

“There were grants about beautifying neighborhoods like ours with art,” he said. “There was probably $150,000 on the table to pay someone else from outside to do the work. My neighbor Wildstyle came up with a list of 45 artists in a four-block radius around where we live. We ended up getting that grant, putting that money into the hands of people with talent right here in the neighborhood.”

While outsiders may be challenged by negative perceptions about life in a low-income neighborhood, residents themselves may be challenged by them as well. That was the case with Wildstyle Paschall, an illustrator for The Learning Tree since 2015.

Paschall, who is also a music producer, photographer, activist and author, remembers the time he first had a conversation with Harges. After learning about the work Harges was doing in their community, as well as his consulting experiences abroad and nationally, Paschall had a moment of disbelief.

“I’m thinking, ‘Why are you still in this neighborhood?’Here is a guy living on the same street as me and he’s done all these things and has been to all these different places,” Paschall said. “I realize he’s not the only person in the neighborhood who has been around and done some things, but that was kind of a blind spot.”

Paschall said that exchange made him realize how easy it is to perceive low-income neighborhoods, including his own, as having only deficits.

“It’s easy to feed into that mindset that the residents have nothing to offer,” Paschall said. “It’s easy to essentially write off everybody who is impoverished. Everyone has the capacity to be doing great things, and many times they are doing amazing things. We’re just not seeing that in each other, even in our own neighborhoods.”

Tysha Ahmad, the owner of Mother Love’s Garden, was among a group of neighbors who took the initiative to address needs following the simultaneous closures of grocery stores in several nearby neighborhoods. She decided to retire from her work in the insurance industry to become an urban farmer to support a co-op that closely follows the ABCD model.

“Those who have the means pay more for a bag, which helps cover the costs for those who don’t necessarily have the means, including seniors and those who have SNAP or EBT,” said Ahmad, who met members of The Learning Tree while working in one of her neighborhood gardens.

Following that interaction, The Learning Tree has supported her urban farming enterprise, which now regularly hosts a five-week summer camp in the neighborhood to teach youth about produce gardening, careers in agriculture and the health benefits of vegetables and fruit.

Going out into neighborhoods

As Paschall noted, The Learning Tree’s efforts model Jesus’ ministry in some ways. “He was out in the streets. He set the standard of going around, talking to people and creating that community,” he said.

Too often, Harges said, good-intentioned people deny others the opportunity to use their gifts, primarily by focusing exclusively on the needs of those they’re wanting to serve.

When you serve those around you, are you focusing on needs or gifts?

“The only thing that they’re asked is, ‘What help do you need?’ ‘What food giveaway do you want to go to?’ or, ‘How can we fix what we have discovered?’” he said. “Most people, when you talk to them, have dreams, or they want to contribute to something. The need to be needed is across the board. Even in our congregations, we miss the fact that when we hoard all the giving to ourselves, there are other people that need to be needed.”

Harges cites one of his favorite biblical texts, 2 Kings 4:1-7, in which the prophet Elisha tells a widow in need to pay her debts by going to her neighbors and asking to borrow jars. “It didn’t say, “Go to the township trustee or to the food pantry,’” he said. “It said, ‘Go to your neighbors.’”

Congregations, groups or individuals interested in adopting an ABCD approach should start by exploring their own gifts and then finding people to work with to implement those mutually gift-affirming practices, Harges said.

What gift-affirming practices are already present in your work?

As a nonprofit, The Learning Tree has not sought out many grants besides a few small-sized grants to help run the summer bike shop for youth, Wolf said. Most of their work, including payments for managers who run programs, is funded by 20% of the income generated by their consulting work, she said. The Central Indiana Community Foundation also supports the nonprofit’s roving work through a partnership that focuses on a community ambassador project.

Deputy Mayor Bennett said that churches are ideally positioned to make an impact in the same way.

“Church members and non-church members, including residents, have their own social capital. It’s easy for us to get caught up in what we don’t have,” Bennett said. “Churches are uniquely positioned to look at what their community does have. … You have so much wealth, so much experience and so much capacity in unforeseen areas.”

Efforts like The Learning Tree can lead to a new way of thinking about what should be considered a healthy neighborhood. A healthy neighborhood isn’t a rich neighborhood, Bennett said. It’s a connected one.

How connected is your neighborhood?

Questions to consider

- How do you provide opportunities to talk about what brings people joy?

- What are you doing to uncover gifts and talents in your community?

- When you serve those around you, are you focusing on needs or gifts?

- What gift-affirming practices are already present in your work?

- How connected is your neighborhood?