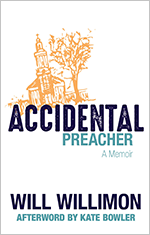

“I don’t trust myself, and I don’t trust memoirs,” Will Willimon said in talking about his new memoir, “Accidental Preacher” (Eerdmans 2019).

A book focused on his own background and himself generally was not appealing to the former United Methodist Church bishop, but after years of requests from Bill Eerdmans and others, Willimon said, he finally wrote a memoir.

Rather than telling straightforward stories about his life and ministry, he instead focused on the impact of God’s interruption in his life, calling him to be a Methodist preacher.

“The most interesting thing about me is I’ve been called,” he said. “And my life wouldn’t have been of great interest had I not been called.”

The book could be seen as a series of sermons on vocation, he said. And as one might expect from Willimon sermons, the words are at times moving, at times funny and always full of great characters.

Willimon has written more than 70 books, which have sold more than a million copies, and has served as the dean of Duke Chapel in addition to his appointments as bishop and professor of Christian ministry.

He spoke about the book and what he hopes others will draw from the memoir with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: In terms of structure, this book is not like a typical memoir. It’s not very chronological; it’s more a progression of themes or maybe a chronology of a call. Can you explain the format?

Will Willimon: Yeah. I wanted it not to be like a lot of memoirs. Chronologically, it is all switched around.

This sounds arrogant, but a kind of memoir that has carried me throughout my ministry has been Augustine’s “Confessions,” which I’ve always read as a sly sort of autobiography.

Augustine begins by saying, “I don’t know why you’d be interested in my life, but let me tell you about my life.” But then midway through, he realizes, “Gosh, I thought this was about me, but it’s really about you, God, and what I thought was my own yearning and striving and questioning was you all along.”

I like that -- to me, that kind of luring us in. I’m going to reveal something about myself, which then lures us toward God and saying that my life is more a product of God’s authorship than mine. That’s always appealed to me.

My title was going to be “Accidental Preacher: A Memoir of Vocation.” Vocation is, I think, the only thing interesting about me. So if there’s any theme carrying through, I’d like it to be evocative God, one who calls.

Then I wrote the thing. You’ll note that each chapter section begins with a Scripture quote, and then in a sense, each chapter is like a sermon arising out of the Scripture text. So I did want to play around with the whole notion of a memoir.

F&L: And speaking of the scriptural preludes, one is from Acts, about Ananias being sent to open Saul’s eyes, and later you mention that you went to this camp in your youth and roomed with a black 13-year-old named Charles who “skillfully cracked open” your eyes to race. Can you talk about your journey with regard to race as a child of the South?

WW: That’s a theme that runs throughout the memoir. I was born in a legally segregated society, and there are moments of the memoir where I talk kind of warmly about my background, but the trouble is, it was racially segregated. I mention the lynching that occurred when I was 1 year old that was never mentioned to me growing up in my town and that I wrote a book about later. So I do think that race played an important role in my story.

I think race has been an important factor in every American’s story; it’s just that some of us recognize it and others haven’t yet recognized it. In places, I say I think I have some sense of my own finitude and that of my family, of my background, of my culture, because of race.

I’m from South Carolina. I know a lot about sin, OK? I’ve got that down. I know what sin is.

F&L: Can you talk about what you call your “discovery of God” in Amsterdam, when you had drinks with Carlyle Marney?

WW: Yeah, I think I look at that as pivotal in the book, and everything moves toward that. I was very lonely as a child and all, and I wanted to be summoned by something bigger than myself. And in Amsterdam, there as a college student, living the good life, I was called to be a preacher. It was quite jarring, and it also was not something that I wished.

And of course, we’ve got a whole mythology of that in Scripture, about God’s call not being something pleasant. And that’s how I experienced it. I experienced it as kind of humiliating.

In my life and in a couple of places in the memoir, I’ve experienced the humiliation of God, realizing I want to be a Methodist preacher. I wanted to do something worthwhile, [then] “Lord, I’m going to be a Methodist preacher.” It was embarrassing.

And that was how I remember it, but also it’s the nature of vocation. Somebody else has got to help you into it, and I feel fortunate I had Marney, who was such a character. And the call has ambiguity, too. I’m not that nice a person, and I’ve done some stuff I shouldn’t have done, and God doesn’t care. So I hope the memoir shows some of the radical, paradoxical nature of vocation.

F&L: You talk about Peter Gomes, the former minister at Harvard’s Memorial Church, and both of you being part of “mainline Protestant hegemony’s last collegiate hurrah.” Can you elaborate on that and what you, over the course of your years, have seen shifting in higher education and college chapels?

WW: Part of it is some of my own insecurity and feeling out of place in higher education -- maybe that comes through occasionally in the book. There’s also some of my disdain for some of the pretensions of higher education, which I don’t really defend. There’s this kind of adolescence in academia.

But I think in all my years in higher education, I’ve always thought of myself as a visitor. I’m a Methodist preacher. That’s the one thing I’m really, really sure about. That’s what God wanted me to do and who I am and who I am at my best. And I’ve thought that even though I’ve spent all of my adult life in higher education in some way, my self-understanding is that I’m a preacher.

That may be delusional. I may be more a product and inhabitant of higher education than I feel like. But I tell in the book of a couple of times where colleagues have said to me that my scholarship is superficial and my writing is too prolific and popular. When I’ve been told that, I’ve just thought, “Thanks. That’s what we preachers strive for.”

But Peter Gomes was kind of my model for campus ministry. He was African American, gay, Republican, born in Massachusetts, with a British accent, and the thing I loved about Peter was he was just so wonderfully, so defiantly Christian at Harvard.

And to me, he modeled how to be in the university. It’s good that they pay well and all, but your job is to be a witness and to have fun with people who think they’re atheists, people who think God is some kind of archaic leftover.

But he also helped me realize what a privileged place the university is, because you get to be with people during one of the most interesting times of their lives. The students seemed to be so much more open and less prejudiced against the Christian faith than faculty, and I loved that.

F&L: What do you hope that people will draw from your story?

WW: It depends on the people. I’d be glad if I just had a letter from someone who said, “Wow, I didn’t know being a pastor was this adventuresome and so much fun. I’d like to talk to you about coming to seminary.” I hope people will lay claim to their own vocations.

I also would like it if the book would be evangelistic in the sense that I just think we have an interesting God who is no more interesting than in acts of vocation. You read the call stories in Scripture and the people God chooses in Scripture, and the Trinity is just never more interesting than when the Trinity is busy calling the wrong people at inopportune times.

F&L: From the title of the book, what would Christians gain from thinking of their lives as “accidental”?

WW: I really believe that we are most us, as selves, due to accidental factors -- by “accidental” meaning external factors, that which is imposed upon us.

I tell the story about how I got my name. You get your name from your family without any say-so in the matter, and then I got my name “Will” from a schoolteacher who just said, “No, William is not right for you; you’ll be Will.”

More than we seem to like to admit as Americans, we are the sum of our relationships and the sum of our connections and all, and so that’s what I was trying to play with the “accidental” -- that things we consider just sort of fluky and happenstance are deeply determinative of us.

And I think one thing I like about Christian ministry is, in a way, it sort of rescues you from your self-conceived story. It writes over your life a story that you’re not the chief author of. And I think that’s a very un-American thing. It’s not a popular word around here, I’m sure, but it’s my last word.