Every Christian leader ought to know that the greatest commandment is to love God, and the second greatest, which “is like it,” is to love our neighbor (Matthew 22:36-40; see also Paul in Galatians 5:14). Love of God and love of neighbor was the way the vast Jewish law was organized into a more basic pattern of life. Jesus, of course, knew this well and drew the connection for his audience: when you love the God of Israel, you are to love your neighbor.

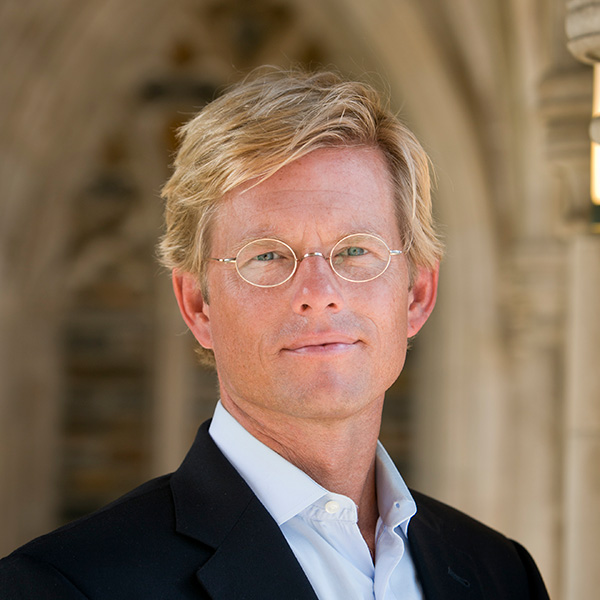

The trouble is that our neighbors have vanished. We know our families, we know our co-workers, and we know our “friends” from the Internet or special interest meetings on everything from sports to fishing to favorite books to politics. But we do not know our neighbors. Or such at least is the thesis of Marc Dunkelman’s new book, “The Vanishing Neighbor.”

Dunkelman argues that the social architecture of America has profoundly changed. Broadly speaking, we used to have three basic rings of relationships or connections: our families (inner ring), our neighbors (middle ring) and our distant acquaintances (outer ring). “Neighbors” were not just those who lived near us but those with whom we could “carry on conversations about personal subjects even if they aren’t entirely private: the birth of a child, for example, an ongoing illness, or a funny coincidence from a few years back” (97). Neighbors were those who knew something of our lives.

What buttressed neighborly connections, Dunkelman says, was “institutions.” Whether the Elks Club, the PTA or even the network that was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, it was this broader institutional organization that made our connections possible and gave rise to our knowledge of our neighbors. In the days before email and all its cousins, our contact with each other was through multifaceted associations that brought us together and enmeshed us in wider, if not directly intimate, knowledge about each other’s lives.

As a whole, Dunkelman observes, these institutions have all but disappeared. And with them have gone the middle-ring relationships.

It’s not that we have quit caring about some of the work these institutions did. It’s rather that we no longer think we need them. They have been replaced by forms of media that allow us to connect directly with those who already share our interests. No longer do we need to gather with others to pursue what we see as “good” or even just to get to know people. We simply go online, discover people who fit what we have in mind and communicate with them about the interest or experience that led us to begin the search.

“Two people with nothing in common beyond a single point of interest can engage without worrying about other beliefs that might put them on opposite sides of a vast divide,” Dunkelman notes (111). People who share the same disease, who collect the same items, who cheer for the same college team, who support the same politicians and so on all connect with those of like experience and thought.

To be sure, a thick network can emerge from such connections, and there is deep good in finding others who have, say, gone through the same chemotherapy. We can also achieve remarkable goals through single-minded focus: issue-based activism has never been as popular as it is now.

But over time, the dangers are that such networks become more like “networked individualism” or even “communal narcissism” than places where we know and are known (111). And our longing for community goes unfulfilled. In fact, it actually deepens. Even the sickest want to know and be known. In Dunkelman’s terms, we have loaded up on single-bond ties or outer-ring relationships and lost the shared sense of life that we long for.

Dunkelman doesn’t really offer any “solution” to the erosion of our middle-ring ties, principally because he realizes that we can’t turn back the clock (and often wouldn’t want to).

He does, however, recognize that without middle-ring relationships, we leave huge holes in communal life and lose the ability to integrate our lives on the basis of interpersonal knowledge and commitment. Moreover, we lose contact with large groups of people who depend on us and who may not have robust families or share our particular interests.

When a crisis comes -- as it did in the fall of 2006 in Buffalo, New York, where two feet of snow caused extensive shutdown -- the effect of this loss is starkly illuminated. In Buffalo, the isolation and vulnerability of a vast number of elderly people suddenly became apparent. They had almost no connection to others. Absent the middle-ring relationships, these people had been largely lost to view. That this is happening yet again in Buffalo is an indication not so much of a lack of will to help as it is once again of the fact that without middle-ring community, we cannot see our neighbors.

It would be a mistake to think that the role of the church (and/or its institutional extensions) was simply to take the place of the institutions that made the relationships of the middle ring. And yet there is a sense in which the church is still the place where the inner and outer rings come together, where our families and our most distant connections are put together through rubbing shoulders with our neighbors, and where we learn of our more immediate communal needs and opportunities. One of the major tasks for leaders of Christian institutions over the next many years will be to discover how to build ties that move beyond the immediate family and are much thicker than single-bond ties.

The New Testament churches were intertwined with a social architecture entirely different from modern America’s. But we nonetheless see in them the relentless drive to connect Christians of all stripes with each other.

Christians were brothers and sisters, members of a larger networked community that imagined itself as a family. As in all families, there were fights aplenty. But the development of concentric rings of ties -- from the most familiar in the household to the broadest reach of Mediterranean cities -- was an indispensable ingredient in the Christian sense of identity.

Being church was not just about supporting local life in the more narrow sense, nor was it simply a special interest in the way that baseball or bass fishing is. It was instead a dense and networked set of relationships that reached across the spectrum from family to neighbor to merest acquaintance to the entirely unknown brother in another place. In short, the early church was a burgeoning institution that created the connections that allowed Christians to become visible to one another across time and space.

If Christian communities are to thrive in a society that has lost its middle rings, we will have to make the connections that render us visible to one another. We cannot simply invest in our own homes and with special-interest friends.

We have no stake in renewing American middle-ring culture per se, and could not do so even if we desired it. But we do have an enormous stake in knowing our neighbors and in providing the institutional space for Christians to build relationships with their neighbors -- to know and be known.