As All Saints’ Day approaches each year, I think of something that happens weekly in congregations around the world.

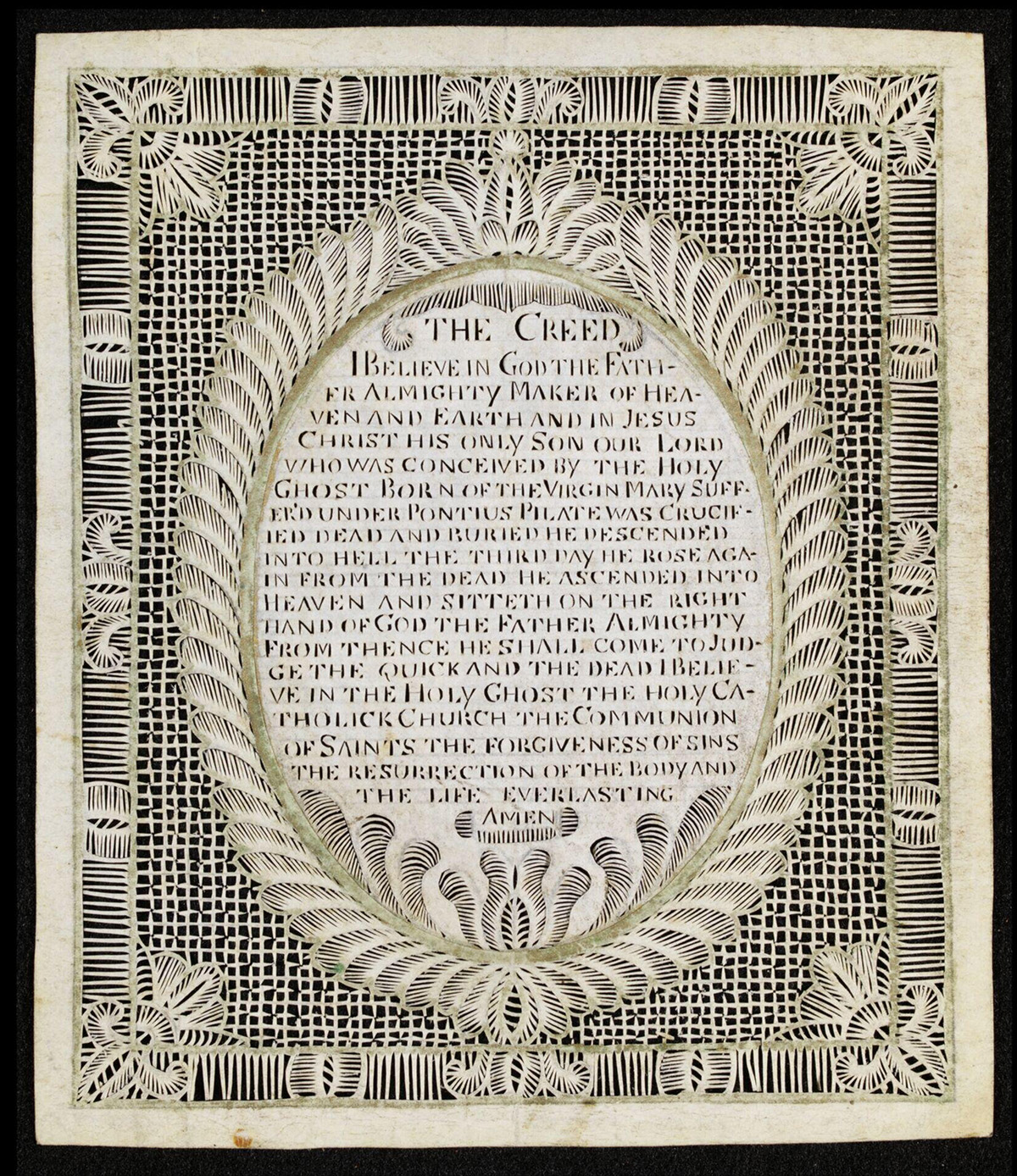

In many churches, the congregation recites the Nicene Creed after the sermon, 220-ish words (depending on your tradition and translation) of orthodox conviction. We rise from our seats, some more quickly than others, some looking down at their paper bulletins while others close their eyes.

It is a lot of words to speak in unison, or in an attempt at it. Unlike a hymn, there’s no melody to guide us along, just the helpful guideposts of punctuation and paragraph breaks. We stop, so briefly, after the first “God,” observing the comma, then move into “the Father, the Almighty.” Another beat. “Maker of heaven and earth.” Beat.

It strikes me how much listening is required in these few minutes of speaking the creed. The listening starts before the creed does: I draw in a breath when we are invited to confess our faith through these ancient words. I always make a game of timing here, trying to start exactly when the celebrant starts: “We believe in one God …” Often I’m off by just a moment and miss out on the first couple of syllables, “We be-,” picking up with everyone else at “-lieve in one God …”

I listen for the pauses, the inhalations. I notice the distinct accent of the woman behind me, how it flavors her pronunciation. Out of the interwoven voices in the room, I can pick out threads: those I know well, those I don’t, those who seem to be scurrying a word or two ahead or lagging a few behind.

It may not sound pretty, but we’ll all wander our way through the same affirmation, and we’ll all end up at that same closing — looking ahead to “the life of the world to come.”

In 2025, we are marking 1,700 years since the First Council of Nicaea. My mind can’t really comprehend the number of times this summation of that council — later amplified at the Council of Constantinople in 381 — has been spoken, read, whispered, recited in innumerable languages. And in how many places — chapels, houses, prisons, cathedrals. The voice I give to these words is one of millions throughout the ages. As Edgardo A. Colón-Emeric, dean of Duke Divinity School, reminds us, “We affirm our faith in English with words originally coined in Greek in response to a Jewish community’s worship of Jesus the Messiah.”

It might be a cliché to talk about “being part of something bigger than ourselves,” but in joining our voices together to say the creed, we’re not just joining the folks in the pews around us. The regular communal recitation of the creed — with all of its potential for both cacophony and harmony — conjures all the saints before us, “so great a cloud of witnesses,” as the writer of Hebrews (12:1) describes them.

It is an invitation to be swept up in that cloud, even on the days we don’t feel like becoming part of it, especially on the days when we long to be. It’s a comfort, a solid ground to stand on, to think that so many of those gone ahead over the past 1,700 years have stood and recited the creed in much the same way we do today: some of us earnest, some of us distracted, some of us (maybe most of us?) a mix of both.

Today, as through the ages, this practice may not sound or look all that glorious — lines will be rushed, words will be forgotten, bulletins rustled or prayer books dropped. But I never want to lose focus on the listening that’s required of all of us as we wind our way toward the creed’s end.

Most of us do not charge our way through the creed, speaking at whatever speed and cadence we want. We listen to those behind, around, beside us to see how they are speaking. And sometimes — hopefully most of the time, but not always — we listen to the deep, confounding truths that we are actually affirming, that were articulated for us 17 centuries ago.

It may sound unpolished but still finds its own harmony. I can think of few better ways to join that great cloud — all the saints — earnest and distracted and trying-our-best alike.

“Amen,” says the woman behind me as we reach the creed’s end. “Amen,” I say — the same word, just a split-second behind the other saints around me, adding to the many millions of “amens” before it.

It may not sound pretty, but we’ll all wander our way through the same affirmation, and we’ll all end up at that same closing — looking ahead to “the life of the world to come.”