Trigger warning: This story includes a graphic photograph of a lynching.

There’s no vibrant iconography or stained glass in the sanctuary of New Beginning Missionary Baptist Church. Housed off rural U.S. Highway 76 in Clinton, South Carolina, in a commercial building that was once a shooting range, the church resembles a Cracker Barrel from the outside, minus the rocking chairs in front. Inside, rows of purple upholstered chairs face a riser -- the makeshift altar.

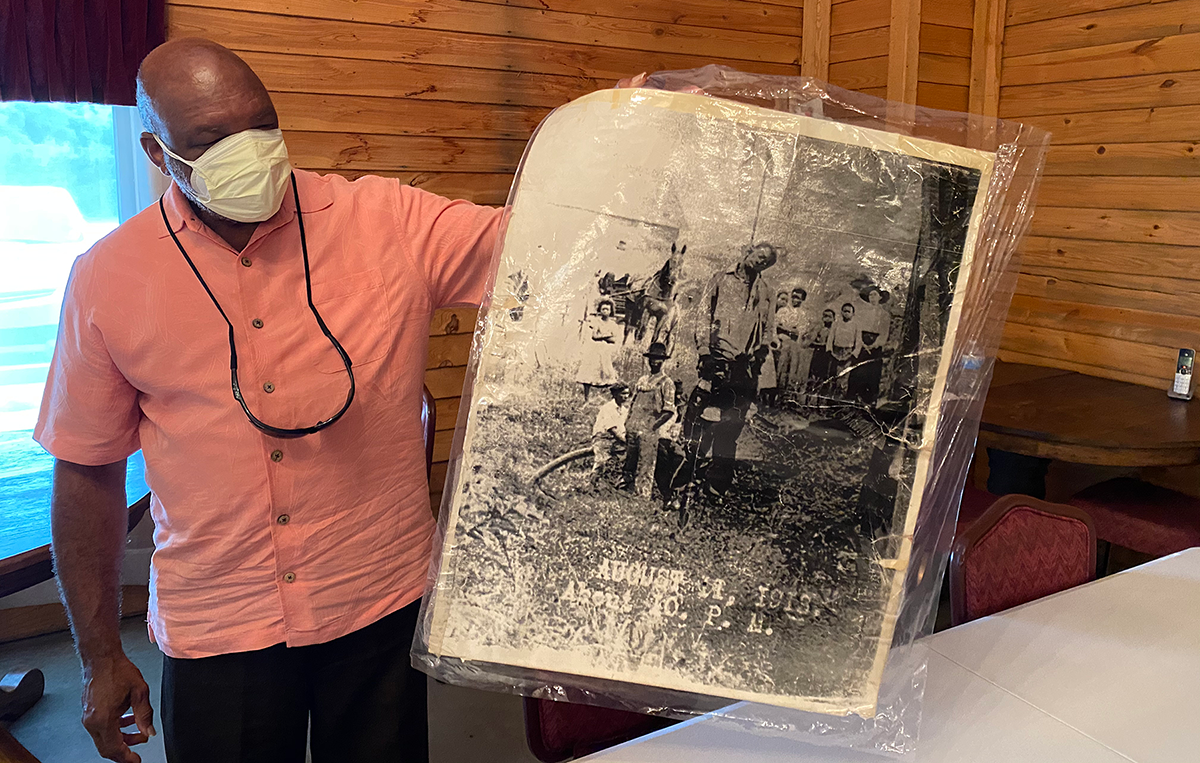

On a folding table in the back of the sanctuary, there is powerful imagery of a different sort. A sepia-toned photograph enlarged to poster size serves as a reminder of what fuels the Rev. David Kennedy’s decadeslong ministry for justice.

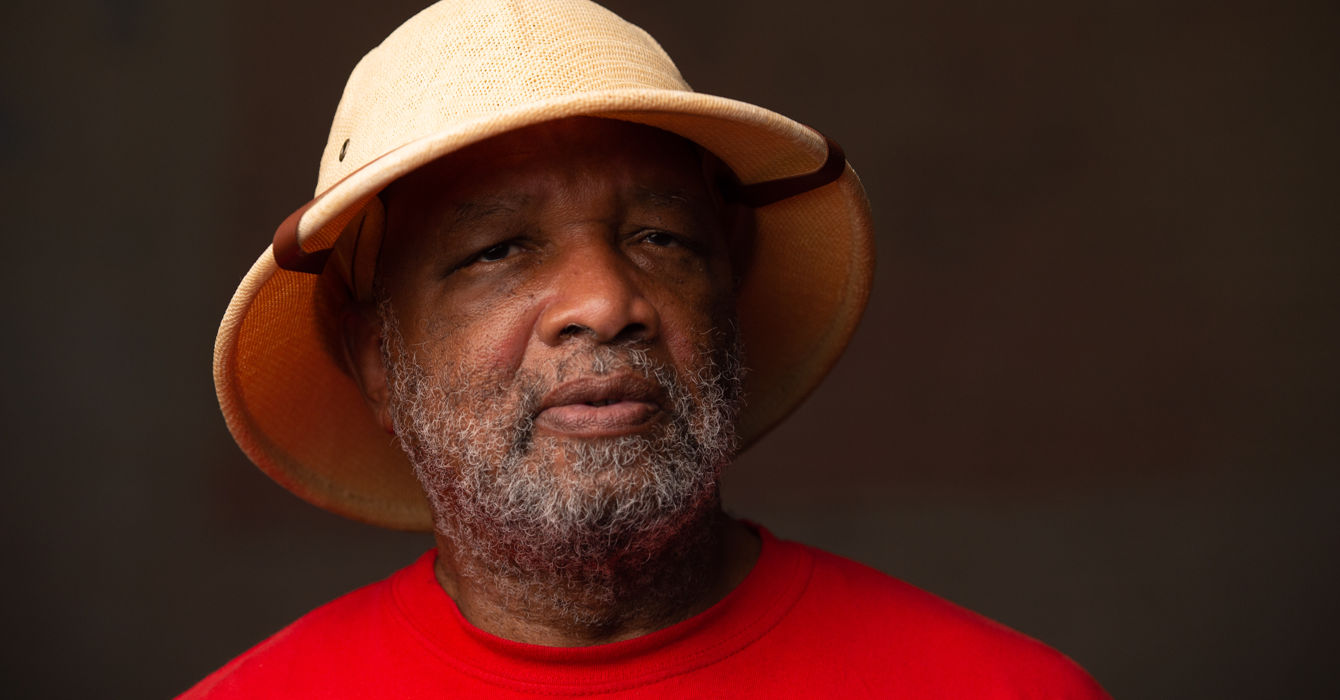

“This is my great-great-uncle Richard Puckett,” Kennedy said, holding the faded photograph from Aug. 11, 1913. It depicts Puckett’s lynching in nearby Laurens, the small cotton mill and farming town where Kennedy, now 68, grew up. His family has lived there since an enslaved African ancestor arrived in the Piedmont before buying his freedom in 1819.

“That noose was still hanging from the railroad trestle well into the 1980s,” Kennedy said. “They left it there to send a message to us Black folks.”

That message was repeatedly reinforced as a younger Kennedy navigated discrimination in the Jim Crow South. It was subtly delivered in every aspect of life, from housing to schooling. In his senior year, Kennedy was among the first to integrate Laurens High School.

And it was a message that reverberated whenever Kennedy went with childhood friends to see movies at the town’s Echo Theater, with its separate entrance for Blacks, who had to sit upstairs in the “colored” section without restroom access.

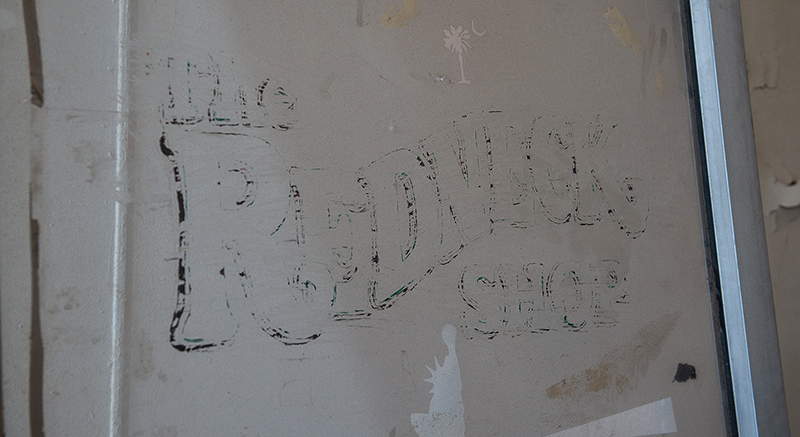

Decades later, in front of that same building, Kennedy led protests against the Ku Klux Klan museum and overtly racist business, The Redneck Shop, that had opened in the former cinema. The shop sold Confederate and Nazi memorabilia, klan robes and “Southern pride” merchandise.

Then through a Hollywood-worthy twist of fate, the pastor came to own the historically fraught space. Today, he and his church are working to turn it into a center for social justice and racial reconciliation, ensuring that a radically different message will echo from the old theater.

Rehab hate, rebuke evil

The Echo Project, as encapsulated by its hashtag, seeks to #RehabHate. Working with the nonprofit’s board and executive director Regan Freeman, Kennedy is pursuing a vision to transform this former KKK stronghold into a center for education, outreach, inclusion and truth telling.

“When it opens, I want the world to know there’s a place in Laurens County that accepts you as you are, where diversity is celebrated and people can engage in open conversation,” Kennedy said, noting that white supremacists will be welcome too. “We’ll say, ‘Let’s talk about why you think the way you think,’ and hopefully, they’ll leave with a change of heart.”

The significance of that hope is not lost on those around him.

“I can’t even remotely imagine what it must have been like to grow up and see that noose by the railroad crossing for years, knowing that your family member was hung there,” said Rauch Wise, an attorney in nearby Greenwood, South Carolina, who has known Kennedy for years -- and knew of him even earlier. “I’d read about him in the papers. He’s always been outspoken, a man of faith protesting against injustice.”

Long before KKK leader John Howard opened The Redneck Shop around 1996, Kennedy was well known in the greater Laurens community for standing against oppression.

Kennedy organized anti-drug rallies in the mid-1980s. He was a vocal critic of what he considered racist policies by the Laurens County school board. As a staff member of the statewide Carolina Alliance for Fair Employment (CAFE) in the 1990s, he advocated and marched for fair wages.

Susan Dunn, the head of legal affairs for the South Carolina ACLU, got to know Kennedy as a fellow labor-issues advocate with CAFE.

Who is working to “rehab hate” in your community? How is the church participating in this work?

“He was quick to take the lead, and always in the middle of the action,” she said. “But he’s not a preacher prone to taking up every inch of air. When you are with him, he makes you feel like you’re the only person in the world.”

A soft-spoken man when not at a podium, Kennedy doesn’t fit the model for a rabble-rouser, but the prophetic spirit of his faith calls him to truth telling.

“I see protesting to honor Jesus Christ as rebuking evil. When we’re protesting, we’re rebuking evil, as Jesus commanded us to do,” he said.

Kennedy acknowledges that his early consciousness about right and wrong, good and evil, was shaped by that relic of frayed lynching rope. But equally formative were the stories learned in his grandmother’s Sunday school class.

Kennedy’s maternal grandfather had been instrumental in establishing Greenville’s Springfield Baptist Church, where the young Kennedy spent Sundays and Vacation Bible School days absorbing his grandmother’s telling of baby Moses in the reeds, and of David and Goliath.

How is Kennedy’s dual formation through the frayed lynching rope and the lessons of Sunday school similar to or different from your own formation? How does this formation show up in your daily life?

“I particularly liked the David story,” he said, winking at his biblical namesake.

Growing up, Kennedy became determined never to cower but to confront injustice. His high school classmates recognized and encouraged these traits. Marvin Stephenson, one of his oldest friends, once told Kennedy he was “an invisible man, until conflict arises -- then you come out of the darkness into the light to lead, so comfortable challenging anything you consider wrong,” Kennedy said.

After high school, Kennedy enrolled at Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, which had been founded to prepare freed people of African descent to be a “power for good in society.” He thrived there intellectually and began to consider American history and “the burden of oppression, the devastating consequences of destroying cultures,” he said.

The life of the mind fueled him, and to this day, said Kennedy -- who still quotes his professors -- “When I get down, I find me an academic book.”

Kennedy and his wife, Janice, moved in 1972 to Nashville, where he pursued a master of divinity degree at Vanderbilt Divinity School while Janice studied education at Peabody College. Kelly Miller Smith, the Vanderbilt longtime assistant dean and preeminent theologian, Baptist preacher and civil rights activist, was a mentor.

New beginnings

Toward the end of his final year at Vanderbilt, however, Kennedy’s in-laws both died unexpectedly, and he brought his bereft wife back to South Carolina. He was ordained at Springfield Baptist Church and began his ministry in small churches in rural Piedmont communities.

In 1984, he resigned a post in Newberry, South Carolina, eager to realize his vision for a new church -- one committed to “feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting those in prison and finding a way to liberate the captive,” he said. “Our vision is to be a 24-hour Christian beacon for God’s bruised, oppressed, exploited and downtrodden.”

That was the charter for Kennedy’s New Beginning Missionary Baptist Church in Laurens. The church began small, meeting in a deacon’s house, then moved to a barn and later a school.

“Eventually, we took over an old Presbyterian church before buying 28 acres and building our own church, complete with a DHEC-certified kitchen,” Kennedy said, noting that the Laurens County Soup Kitchen, feeding some 250 people a day, and on holidays up to 1,500, is a signature community ministry for New Beginning.

That church building with its professional kitchen burned, somewhat suspiciously, in 2012, but the congregation maintains a soup kitchen out of a restaurant neighboring its current location.

“When I moved to Laurens 10 years ago, I saw this inspirational man continuously reaching out to people in so many ways,” said Harry Agnew, a local businessman who serves on The Echo Project board. “Where there was a need, he’d fill it. He’d try to make it right. The people who line up for the food his church distributes -- they really and truly need it.”

How does Kennedy’s commitment to embodying Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 25:34-40 call you and your community to an active faith?

When Kennedy encountered a man with his wife and two hungry children living out of their truck one day in the mid-1990s, he did what Christ calls him to do and what he’d done for many over the years.

“I asked if those kids had eaten yet today,” recalled Kennedy, who got them some clean clothes and a shower and treated them to a buffet dinner. “If you follow Jesus, his command is not up for negotiation. You feed the hungry. You don’t ask who.”

In this case, “who” happened to be Michael Burden. Kennedy recognized Burden as an associate of John Howard, the white supremacist behind The Redneck Shop. Burden had been a statewide klan leader and Howard’s protege.

After a falling-out with Howard, Burden and his family were homeless and penniless. An unlikely friendship began between Burden, his wife, Judy, and the preacher who heretofore had been the bane of Burden’s existence.

The pastor’s relentless protests against The Redneck Shop and the klan’s presence in Laurens had threatened to shut the operation down and garnered national press, drawing Jesse Jackson and others to march alongside him.

Now, thanks to the cautious but unconditional grace from the predominantly Black congregation at New Beginning, Burden was walking alongside Kennedy, joining the pastor’s family for meals, living in housing donated by a church member, attending worship services and working toward a new beginning in his life.

Howard, at one point, had signed the old Echo Theater building deed over to his young disciple. In a bend in the arc of history, Burden then sold the deed to Kennedy and New Beginning Church for $1,000 in 1997. His one stipulation allowed Howard use of the building until he died.

The shop closed in 2012, after also serving for five years as the headquarters of the American Nazi Party. Left behind after Howard’s death in 2017 was a legacy of hate and division. The dilapidated theater, located a block away from the Laurens courthouse square and its Confederate monument to the “Boys in Gray … Our Heroes,” was ready for a next act.

Real to reel

The saga became a feature film “Burden,” winner of the 2018 Sundance Audience Award. Wide release followed in 2020.

Directed by Andrew Heckler and starring Forest Whitaker as Kennedy, the film has brought international attention to The Echo Project and boosted ongoing efforts to raise the estimated $3.3 million needed to fully renovate the century-old building and open the center.

This spring on May 27, Kennedy, executive director Freeman, the board and members of the community celebrated a milestone, as the vintage E-C-H-O lights above the marquee were restored in bright yellow neon and lit for the first time in 25 years. Walmart presented a $75,000 donation in support of the project’s mission at the lighting ceremony, boosting the total raised to date to just under $590,000.

Meanwhile, Kennedy and the congregation of New Beginning continue trying to live the gospel and bring the healing of Christ to the community. The pandemic has taken a toll, with congregation numbers now hovering around 50 people. Michael Burden eventually moved away from Laurens after an arrest and prison stint. Kennedy and Judy Burden remain friends, although she is not a church member.

“Rev. Kennedy is a man of deep faith. He’s always stood for Christ and is not afraid to live by the Bible’s teachings. That’s what it’s all about,” said the Rev. Clarence Simpson, a longtime member of New Beginning who serves as pastor of nearby Wateree Baptist Church. “[New Beginning] has never been a large church. It’s a small congregation with a real big heart,” he said.

Kennedy knows it will be an uphill climb for the church to complete The Echo Project. But he’s encouraged by the energy and enthusiasm of Freeman, a white Laurens County native and recent college graduate whom he calls “a breath of fresh air,” and by the support of the mayor and town council, as well as many business leaders, including board member Agnew. They hope The Echo Project will serve as an economic catalyst to help revitalize the struggling downtown.

“We want to make sure Rev. Kennedy’s mission of inclusion and outreach continues for the next generation,” Agnew said. “It’s a lifetime mission. We saw it clearly on Jan. 6 -- there will always be work to do to make people aware of the need for diversity and acceptance.”

As Kennedy walks through the theater, past overturned counters that once displayed Confederate tchotchkes and glass doors that still bear the faded remnants of “Redneck Store” lettering, his spirit of hope burns bright despite a life of witnessing prejudice and injustice.

“What keeps me going?” he asks. “I am sustained by my understanding of God, and by a super wife. She fights when I fight."

“God gave me a spirit to stand against the world and to stand up for the worst of us, the least of us. I love to find meaning in the suffering. I work better, I act better, I hope better,” Kennedy said. “We have to find a way to love one another, and we can’t do that on our own.”

What spaces in your community are ripe for physical and spiritual rehabilitation?

Questions to consider

- Who is working to “rehab hate” in your community? How is the church participating in this work?

- How is the Rev. David Kennedy’s dual formation through the frayed lynching rope and the lessons of Sunday school similar to or different from your own formation? How does this formation show up in your daily life?

- How does Kennedy’s commitment to embodying Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 25:34-40 call you and your community to an active faith?

- What spaces in your community are ripe for physical and spiritual rehabilitation?