After writing “Native,” Kaitlin B. Curtice felt burned out. The book was about moving through grief and hope in the midst of Indigenous identity and working through the impact of colonial American Christianity.

“For me, after writing ‘Native,’ I needed the next step,” she said. “If this is the reality and these are the things that I’ve experienced, what comes next?”

Her answer comes in her most recent book, “Living Resistance: An Indigenous Vision for Seeking Wholeness Every Day.”

In the book, Curtice tries to bring readers to the understanding that knowing about oppression isn’t the same as embodying healing in one’s own soul and in the world. By presenting cycles and seasons of life intertwined with Indigenous wisdom, she helps readers through the process of reconnecting parts of lives severed by colonialism.

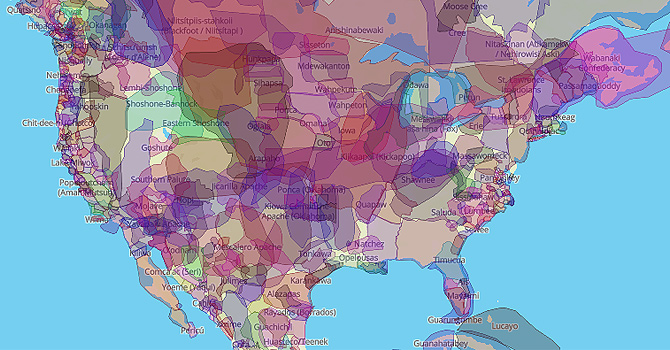

Curtice is a celebrated speaker and author and an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

She spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about the book and how resistance can be a force to encourage us to practice a life different from the one we’ve learned from colonialism.

Faith & Leadership: What led you to writing this book?

Kaitlin B. Curtice: This book felt like a natural next step after “Native.” “Native” was a difficult book to write. It delved into my experiences, my identity, our collective identity as a nation, as Christians, and my journey with American Christianity and what to do with it as an Indigenous person.

I write in my new book that I had a really difficult burnout after writing “Native,” which came out right as COVID happened. “Native” was so much about my hope for the future, but also the grief of so many of us who are trying to just come to terms with colonization in all of our different identities and experiences.

I wanted to write a book on resistance that would be embodied and would also be for anybody to read, which became “Living Resistance.” I based it on cyclical ways of understanding ourselves and each other and the Earth and our relationship to one another. I wanted it to feel like a journey in this book. The book asks how we resist colonization and also at the same time form a better relationship to ourselves and each other and the Earth.

It still has poetry and storytelling and all the things that I am, but I also wanted it to have that worldwide Indigenous knowledge and wisdom and different experiences of people all over the world who are resisting the status quo of hate or colonization or white supremacy or whatever that thing is that has hurt so many people.

F&L: What is your hope for readers of the book?

KBC: I think my first hope is that people recognize that this journey we’re on is trying to become better humans — trying to love better and trying to resist whatever the status quo of hate is.

I want people to just recognize, take a bit of a breath and recognize that this is a lifelong journey. I write about this in the introduction, but I think one of the saddest things to see is the pressure that we put on one another to change or to create change. What ends up happening is that we go so hard at first and then we burn out.

We read the books we’re supposed to read, but then we don’t actually change anything, because we don’t have the capacity to do it. I just want people to take a breath and recognize that this journey of resistance, this journey of loving ourselves and each other better, of engaging with healing ourselves through loving Mother Earth better, that this is a lifelong journey.

It’s going to take our whole lives, and we still don’t have all the answers, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t work or that it didn’t matter.

I put these little questions or prompts at the end of the chapters, and I call them “resistance commitments.” I just wanted to add a few more things, because ritual and journaling and those kinds of things are so important to me, and I’m sure that they’re important to other people as well.

I love pausing and letting people just stop for a second and kind of process what they’re hearing or what they’re taking in. Because we are so overloaded with new information all the time, I think we need to stop and let it sink in for a second and ask how it could be a part of our everyday lives.

F&L: Why “resistance” versus other words, like “resilience” or “abundance”?

KBC: Resistance is a force, like friction. It’s pushing against something else. It’s preventing or slowing down the motion of something.

In this book, I wanted us to think about resistance as a way that we use our everyday lives to push against, to exert energy against the status quo of our time, whatever that might be — if it’s hate, if it’s white supremacy, racism, all the things that are hurting us or that lead to oppression, that lead to pain in the world.

How can we use our everyday lives, no matter who we are, to exert energy against that? Then I also wanted to stretch it further to say that just because we’re pushing against something, it’s not always just about what we’re pushing against, but it’s also choosing something on the other side of that.

We push against, we resist this status quo of hate, because we’re dreaming of a better world, because we want something beautiful and good on the other side of that. So we have to resist something in order to get to the beauty of what’s waiting and what we get to create.

Because words like “activism” and “resistance” and “decolonization” have become so popular, I’m still worried that we aren’t getting what it really means. What does it mean to practice these things in our lives?

I was just really drawn to this idea of resistance and hoped that I could kind of bend it and stretch it for us to understand, not just as a scientific term, but that it could become part of our lives. I really enjoy being able to do that with words.

F&L: What is significant in thinking about resistance from an Indigenous perspective?

KBC: A lot of this book is grounding us back to the land. It’s grounding us back to Mother Earth, whom we call Segmekwe in Potawatomi, to care for our bodies, embodiment, to care for each other, which is our idea of kinship, and to care for the creatures of the Earth.

That Indigenous wisdom and philosophy has existed all over the world. Throughout the book, in every part of the book, I’m trying to point us back to our child selves as one space of healing but also to point us back to connecting our souls — in our bodies and our hearts — back to the land that we’re on, back to water or earth. These beautiful beings and this beautiful land and space that we have have been given as a relationship.

We resist by connecting back to the land. We heal by returning to our own stories. We heal by telling our stories, and I want that to be accessible in the pages of this book for everyone, because I want healing for everyone, not just for Indigenous people.

I want us all to be healing together, and I think that the subtitle, “An Indigenous Vision for Seeking Wholeness Every Day,” and the vision that I had for this book, this kind of cyclical way of healing, was a really important thing for me to share, and I’m glad I’ve been able to share it.

F&L: Can you talk me through the four realms in the book?

KBC: The idea of a realm can be weird for some people. It reminds them of a kingdom or something, but a realm is just a space that we inhabit.

For Indigenous people, a lot of us have the medicine wheel — a circle with four colors. Those colors represent a lot of different things. They represent the four seasons, the four directions. They represent different life stages. We are taught to follow cycles, to follow the seasons. There are cycles of life and death.

It’s all around us, and so I wanted to create some sort of framework that was cyclical and not linear to help us walk through this. The first realm I call the personal realm, and it represents the season of winter in my book. It’s a time to think about ourselves, to think about who we are and to process what self-care is, what self-love is. What is embodiment? How are we healing our relationship specifically to ourselves?

The communal realm goes to the next step of that. It represents dirt, or earth, and it’s the time to honor our connection to the land and to each other. It’s the season of spring, so you think of it as the time that we’re planting seeds in the ground, the communal work of doing that.

Then the ancestral realm is this fluid space where we’re asking what resistance means on the ancestral level, which will be hard for some people to grasp. I’m hoping that they’ll just lean in and listen, because when we do healing work, we’re healing our ancestors and we’re healing those who come after us one day when we are ancestors — we’re thinking of our time as more than just us. It’s actually about healing those who came before and those who come after, and I wanted to really point to that.

The fourth realm is called the integral realm, and that’s about integration. It’s the very center of who we are. It’s our fire. It’s our soul. How do we take all of this stuff that we’ve been learning and — it’s the season of autumn — how do we harvest that? How do we gather it all in?

I wanted to make it clear that these realms aren’t going to then be lived in in a linear way. You don’t have to go from the personal to the communal, etc., but I wanted the realms to feel like they build on one another and that we inhabit different realms in different aspects of our lives.

We’re working through all of these seasons at the same time, and that’s totally OK. But how can we take the time to focus in on one realm at a time and ask, “How am I caring for myself?” but also, “How am I caring for the land?” or, “How am I thinking about my ancestors while also dreaming of the future and envisioning what prayer is?” and, “How do I bring it all together?”