Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series exploring how the field of game theory can help church leaders navigate conflict effectively.

Two churches I know well sit just 5 miles apart. They belong to the same denomination. Their neighborhoods have experienced nearly identical demographic changes. Yet one church grew slightly, while the other lost more than 10 percent of its members.

Explanations for church growth and decline abound. Sociologists such as Mark Chaves, Robert Putnam and Diana Butler Bass offer powerful explanations for North American church decline, highlighting the significance of birth rates, demographic changes and other macro trends like the rise of the nones (which has always sounded to me like an action movie title).

Others such as Jackson Carroll, the author of “God’s Potters,” remind us of the importance of pastoral leadership. While church leaders need to pay attention to all these theories, none of them accounts for the vital role that congregational culture plays in growth and decline.

How much, and in what ways, does congregational culture affect membership and attendance? I used game theory to design a study to try to answer that question. Employing what’s called the “public goods game,” I looked at the level of cooperation in church leadership bodies -- a measure that I believe is reflective of the larger congregation.

Why the public goods game? The prisoner’s dilemma game discussed in the last article can help church leaders navigate conflicted relationships between individuals. Congregations, however, are rich and complicated communities.

To understand communities, game theorists look to the public goods game, a multiplayer version of the prisoner’s dilemma. The public goods game functions like a church potluck.

Church potlucks work best when everybody agrees to bring a dish and sticks around to help clean up. But the reality is that some people defect: they show up empty-handed or leave without pitching in.

When most people cooperate by sharing food and cleaning up, potlucks go well. When enough people defect, however, folk begin to grumble. Game theorists believe that the public goods game can help measure a community’s level of cooperativeness, which correlates with a group’s ability to thrive.

Here’s how it works. In a simple public goods game, players receive a set number of units for every round. Each player can choose to share these units -- sometimes actual dollars, sometimes units representing time or energy -- or to keep them.

With every round, each player must decide how many units to donate to the common pool. After all players have contributed, the units in the pool are multiplied by a small factor, often 1.6, and then divided equally and returned to all players.

For example, let’s say 10 players start with 20 units each and each player donates all 20 of his units. At the end of the round, each player will receive 32 units. When everyone contributes, everyone wins.

And yet it can pay even more to defect. Let’s look at the same group of 10 and imagine that nine players give everything but one player gives nothing. At the end, each of the 10 will receive a return of 29 units, so that the defector winds up with a whopping 49. Because of the defection dynamic, cooperation tends to break down over time in this simple version of the game.

More complex versions of the game allow players to reward and punish other players -- a dynamic that more closely resembles human behavior in community. Game theorists have different ideas about whether punishment encourages or discourages cooperation.

So how, I wondered, does this concept play out in the church? Under the direction of Duke University professors Greg Jones and Dan Ariely, I developed a study to find out.

I conducted a public goods game study of 98 elders (ordained leaders) in 11 PCUSA church sessions (governing bodies). I observed participants playing a simple public goods game, as well as one that allowed the ability to reward and punish.

Would congregational growth and decline correlate with the rate of cooperation, reward and punishment? Would leaders in declining churches be more inclined to punish? Would leaders in growing communities be more likely to cooperate and reward?

When I looked at all the congregations together, I saw a slight but statistically insignificant correlation between growth and cooperation and growth and reward. I found no correlation between growth and punishment.

The results became more interesting -- and more helpful for Christian leaders -- when I separated the results for churches with more than 100 members and churches with fewer than 100 members.

In larger-membership congregations, growth correlated strongly with cooperation, reward and the avoidance of punishment. This suggests that leaders in larger-membership congregations would do well to minimize punishment and work to find creative ways to reward members of the community.

A different picture emerged for smaller-membership congregations, where growth correlated strongly with reward andthe imposition of punishment.

In larger-membership congregations, groups with the lowest punishment percentages, around 10 percent, experienced the most growth. One might surmise that if a low punishment percentage was effective, one approaching 0 percent would be even better. But this doesn’t seem to be the case.

In smaller-membership congregations, the groups experiencing the most growth had about a 10 percent rate of punishment, similar to that of the flourishing larger congregations. But smaller congregations with the worst growth -- those experiencing steep decline -- hardly punished at all. Anything less than a 10 percent punishment rate correlated with significant numerical decline.

In “Give and Take,” business professor Adam Grant cites a study that might help explain this phenomenon. Researchers found that strangers competing against each other in a negotiation game fared surprisingly better at achieving joint profits than did dating couples.

The couples, more concerned about maintaining their relationship than being frank enough with each other to compete well, fared worse than the strangers, who were willing to be more straightforward. In a similar way, I suspect that the concern for maintaining relationships in smaller congregations, where it is hard for leaders to get away from one another, may help account for the lower punishment level in smaller churches experiencing decline.

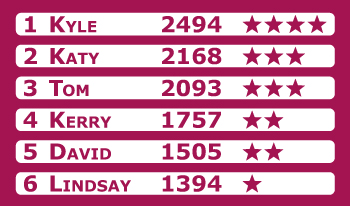

Another fascinating dynamic that emerged from my study was inequality, or the gap between the players with the highest and lowest scores.

In larger-membership congregations, growth correlated fairly strongly with inequality. In other words, leaders of larger churches were more comfortable with some leaders having much higher scores than others.

Smaller-membership congregations, though, were uncomfortable with inequality; the more growth a smaller congregation experienced, the less comfortable the leaders were with some standing out from the others.

It became clear that in smaller congregations, players began to give and reward in ways that would equalize the points for all. If this play reflects reality, leaders of smaller-membership congregations need to be very thoughtful about how they protect leaders who excel. Smaller-membership congregations may tend to undermine, inadvertently, the leaders they most need.

What is absolutely clear from this study is that leaders should reflect consciously on the ways they reward and punish the people around them. Church leaders’ rewarding behavior is usually pretty obvious -- public thank-yous, for instance. But we may not realize the subtle, unhealthy ways we punish one another -- being slow to respond to emails or voice mails, using “distancing” body language in meetings, sitting apart from people we wish to discourage.

Leaders of larger congregations should exercise the greatest possible caution regarding punitive behavior, which can unravel emergent cooperation. Positive, rewarding behavior marks growing larger-membership congregations.

In smaller-membership congregations, positive, rewarding behavior is just as important as it is in their larger counterparts. But in these smaller contexts, leaders of growing congregations must also be willing to impose healthy discipline on members who are not contributing to the common good, speaking the truth in love when it may be easier, in close quarters, to keep one’s thoughts to oneself.

As important as social trends and pastoral leadership are, game theory underscores that church culture is every bit as important. The church already confesses the priesthood of all believers. The public goods game gives us a way of seeing this scriptural wisdom in action -- that all members of the community contribute to an atmosphere of cooperation.

We are left, then, with a question of newfound significance: What are you bringing to your next church potluck?