Memoir and original poetry are two unexpected elements in Willie James Jennings’ newest book. Jennings says he recognized the need to speak differently in order to be heard by some educational leaders who would otherwise discount his voice. It required more than an academic treatise.

“In order to speak to the problem that I was discerning in a way that would speak to the folks who normally would not really want to listen, but also to speak in a way that would create the kind of conversation I wanted to have, I needed a kind of multimodal form of speaking,” Jennings said.

“In order to speak to the problem that I was discerning in a way that would speak to the folks who normally would not really want to listen, but also to speak in a way that would create the kind of conversation I wanted to have, I needed a kind of multimodal form of speaking,” Jennings said.

“When it comes to thinking about education, and theological education especially, there’s a way in which they can hide behind their worlds, their academic worlds, and not really be affected by the things they’re reading. What I tried to do was to write a book from the inside of their defense mechanisms, the inside of their worlds, not to tell the secrets, but to tell all the meaning to the secrets, which brings people into the deep, intimate psychic space where all these troubles are felt so profoundly and so intensely.”

Jennings’ new book, “After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging,” is the first in a multivolume series called Theological Education Between the Times featuring theologians from around the country. ("After Whiteness" was recently named one of the best religion books of 2020 by Publishers Weekly.)

Jennings’ new book, “After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging,” is the first in a multivolume series called Theological Education Between the Times featuring theologians from around the country. ("After Whiteness" was recently named one of the best religion books of 2020 by Publishers Weekly.)

Jennings spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: One recurring theme throughout the book is the model you refer to as the self-sufficient man. What is his role in Christianity and in theological education?

Willie James Jennings: It is the fundamental problem that we’re facing. There are so many conversations about the crisis in theological education, and then also the crisis in Western education.

What I’m writing about in this book is that there is a crisis that superintends those crises, a longer, deeper crisis that is founded right at the very beginning of the endeavor, and that is the image that drives the aspiration for education, and the image that drives the goal of formation, not only in theological education but in Western education.

That image is the forming of a self-sufficient man who embodies what I call three virtues: possession, control and mastery.

The origin of that image in terms of Western education comes back to the beginning of the colonial era, when so many people found themselves masters over vast stretches of land, vast amounts of natural resources, as we would later call them, and masters over so many people’s lives.

As they looked at the world they had control of, they thought to themselves, “I must pass this on to my sons” -- primarily their sons. Women were not thought about as being the bearers of the legacy. “I must pass this on to my son and to his family.”

The question to ask themselves was, “How must my son be formed to rule after I am gone? How might I form my son to be master of all that he surveys?”

It’s inside that desire and that anxiety of wanting to ensure the carrying on of the legacy that so much of Western education is built. So many institutions in this country were built on a plantation, or they were built on land donated by plantation owners or massive planters. This reality of forming self-sufficient men had at its heart a strange use of the idea of the magnanimous man that comes out of the Stoic thought.

That idea about a magnanimous man is one who is not given to extremes -- extremes of anger, extremes of gluttony, extremes of joy -- but who remains centered, in self-control, and it is that one who is able to wield his power responsibly. The magnanimous man is one who never apologizes for his power but uses it properly and recognizes an order to all things that stems from the use of that power.

In fact, it is the magnanimous man who is self-sufficient who then is able to order his world, and it’s that idea, a very powerful, very attractive idea, that lays the foundation for the aspirational formation of all education, especially theological education.

That’s the heart of the book in terms of the problem.

Now, in terms of a solution, a way to move forward, I suggest an alternative vision, an alternative image that should guide our formation efforts. That alternative vision is of Jesus and the crowd, and what’s at the heart of that image is the ability of Jesus to gather people together, to open up the possibilities of a sense of belonging that reaches across boundary and border, hostility and difference, and joins people together.

The desire there would be that aspiration set in place in our educational work, in cultivating people who know how to cultivate belonging, who know how to, in a sense, build communion, so that whatever they do, whatever endeavor, whatever vocation they choose, what will be at the heart of it, what we will see at the heart of it, is not the self-sufficient man. What we’ll see at the heart of it is one who knows how to gather. So that’s the positive goal.

Of course, the problem that I want to make sure people understand is the depth of sickness, the depth of pain, the depth of suffering and melancholy that were created and exist to this moment in so many institutions, especially theological institutions, that are still caught in the pool of all the formation toward that self-sufficient man.

F&L: You explain the idea that to know a thing is to possess a thing, and the commodification that is at play there. Can you talk about that?

WJJ: The problem with the way in which knowledge has been presented to us within educational work has been inside what I call the fragments. There are three kinds of fragments that those of us who live and work in this whole endeavor of education function in.

The first fragment is positive. That fragment comes from Christian faith and Christian life, where we recognize that we have nothing in its complete form. We have it in slices and pieces, and the beauty of it is that we’re invited into a shared project, the weaving together of the pieces.

Then there is the second fragment, which is the fragment created by colonialism, in which people’s worlds were shattered, torn to pieces, and so many students of color come to not only theological education but to other education hoping that the educational process will help them pull the pieces back together to figure out how to work with the fragments that remain.

Then there is that third fragment that you’re referring to, and that third fragment is the way in which knowledge is constantly formed as commodity. That builds from its legacy of knowledge being formed in that way through colonialism, in which as the colonialists came, they sought to possess and to learn -- two sides of the same coin.

It’s the weaving together of possessing and learning, or possessing and knowing, that gave life to knowledge as a commodity. And so the great danger for us is to then think of our educational work [in that way].

We who are educators think of ourselves as intellectual merchants of the commodity fragment. This is a problem, because it again underwrites an idea of control, an idea of possession and, of course, an idea of mastery, so that what one is doing when one touches ideas or one touches concepts, what you are doing is that you are inside a process of capitalist exchange.

What often happens is people lose sight of the lives, the ways of life, the reality, the majesty, a respect for this world that should be fundamental to knowledge.

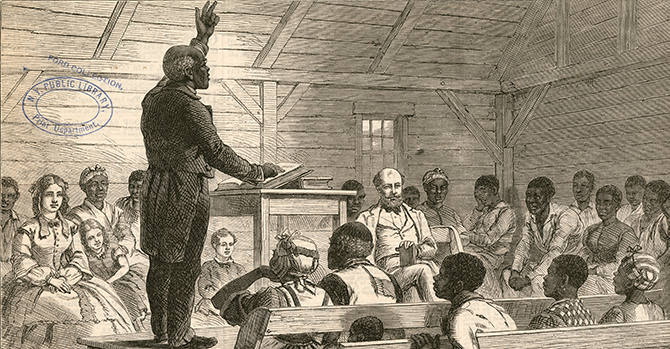

F&L: Could you speak to the racial paterfamilias that you raised in dissecting a picture from an exhibit at Wheaton College?

WJJ: That, in one image, captures so much. The racial paterfamilias is really the underlying infrastructure of institutional life in the West, especially educational institutional life. It goes back to what I mentioned before: the master wanting to establish, in a sense, his eternality through his son and his son’s son, and institutional life being built on the desire to run with the smooth efficiency that was hoped for by the plantation.

The racial paterfamilias is at the heart of that. Racial paterfamilias is a reality of order and operation that builds from the father as the font. And from the father flows the order and operation of everyone -- the father, master, to the mother, mistress, to the children to the servants to the slaves to the animals.

The paterfamilias is the fundamental organizing unit of the “good society,” and the tragedy for us is that so many institutions in the West are haunted by the paterfamilias.

What are these characteristics? It is the inability to listen to people of color. It is the impulse to treat people in terms of their use and value. It is the creation of a reality of alienation for those who see themselves as disrespected and devalued.

It is the underwriting of a masculinist insensitivity at the site of the operation of an institution to be able to fire people with a focused coldness for the sake of the institution, and it is in the end a refusal to see the work of building as a shared project that is meant to show the life of the whole and not just the life of the one, the leader.

F&L: You have a line in that chapter that says, “Not all bullies are hated. Some are imitated because we see in them an efficiency and a clarity of action that fit the way we see the world.”

WJJ: I’ve seen that so many times in so many places, where efficiency is imagined as a good in and of itself.

What so many people don’t realize is that that imagined efficiency reaches right back to the plantation, where if it’s necessary to cut a slave’s arm off to keep them from trying to run away, we’ll do that. If it’s necessary to kill one in order to keep the others in line, we’ll do that. If it’s necessary to sell the children of one in order to make a profit and keep the plantation productive, we’ll do that.

F&L: You talk at the end of the book about bringing hope into focus. Could you speak to that?

WJJ: What I’m trying to do is to help people imagine a different kind of gathering, one in which they see the gathering not in terms of utility. The desire to gather becomes the overarching reality that drives them forward.

That hope in this regard shows itself in their relentless drive to draw people together, to create communion in everything they do -- not just to gather people together, but to gather together people who would normally, usually not want to have anything to do with each other, but they are there because of this person.

And we all know people like that, who -- they reveal the uncanny but deeply appreciated ability to bring folks who are in a terrible place individually and folks who are at odds with others, but because of this person, they will come together.

They will show up because of their deep commitment to this person. They may not be committed to each other, but their commitment to that person means that they’re willing to come, and if they are present, they know that this person will constantly turn them in a hopeful interface that will become more than just an interface with these others they would prefer not to have anything to do with.

There is profound hope in cultivating such people with that capacity so that when they leave our institutions, in whatever field they have been trained, they’ll be good at that particular field. But what they gesture by their life says so much more about what it means to form someone, especially within theological education, to form someone who performs and embodies the image of God.

What would it mean to have somebody who, their entire way of being in the world, they are always looking to create such moments? That’s the signature of their education -- not that they impress you with how they exhibit possession, control, mastery.

That’s the effect of having been highly educated, having been cultivated through a rigorous process that yields this kind of person.

F&L: What else would you want readers to take from this book?

WJJ: I try to bring people inside the ongoing challenges and struggles for so many scholars of color and staff of color in educational institutions, where many move through in a kind of trail of tears, both in terms of their own formation to be in such places and in their ongoing life in certain places, that they constantly have to face this self-sufficient man.

My hope is to be able to name it, because to name it is already to be able to see how to get around it. My hope is to not only name what many have not been able to name but then to offer to everyone a way to walk away from it.

To see for the first time that it is this sick man that’s been positioned at the end of it all means that you can together say, “No. We’re going to move him from that position. He will not be the goal any longer, and we will now have a new goal.”

For the faculty and staff and students of color at theological institutions, my hope is that they’ll see both a naming of what they sense and also a map to start to imagine beyond that, along with their colleagues.