I was blessed to have my predecessor, Gardner Taylor, preach at my investiture as pastor of Concord Church. The lasting image of that service guides my work every day. He invited the eight former pastors to stand with him in spirit as he declared to me, “This people will be undaunted by any challenge.” Best. Preacher. Ever.

Challenges intensified are crises. Periods of crisis have informed my sense of pastoring. I arrived in Brooklyn in the mid-1980s, along with the rise of crack cocaine and the AIDS epidemic.

Ten years into the pastorate, I answered a call from my administrator just before 9 one morning: “Pastor, I won’t be in today -- they just flew a plane into the World Trade Center!” It was September 11, 2001.

Less than 10 years after that, the stock market dove, pushing us into the Great Recession. A few years later, Hurricane Sandy. Each crisis brought its distinctive challenges to life and doing church in Brooklyn. We learned some things in each of these moments, but nothing prepared us for a pandemic.

What are the crises through which your congregation has ministered over the years? What did the congregation learn, and do these lessons apply now?

There were no blueprints for this. Life as we knew it came to a screeching halt as businesses, schools and houses of worship closed.

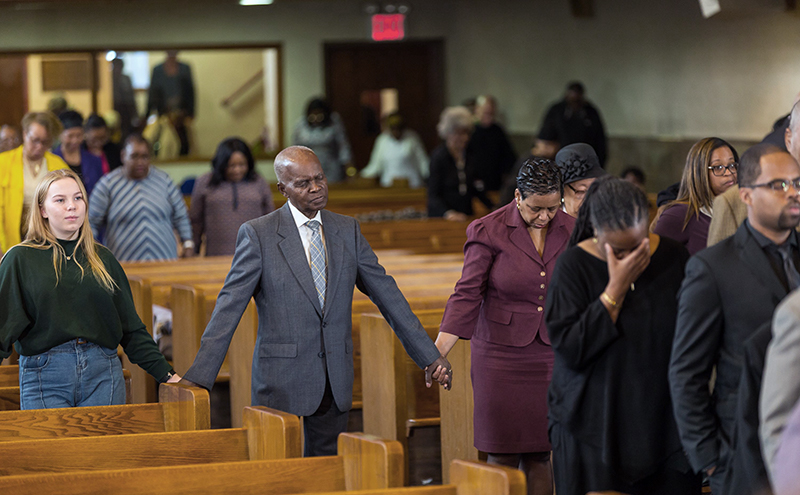

On March 15, I announced that we were going to do our part to slow the spread of COVID-19. It would be our last in-person worship service. We were closing the building and ceasing all operations until, we thought, Palm Sunday.

I was not even supposed to be at Concord that Sunday. I was to be in Dayton, Ohio, to fulfill a long-standing engagement, with plans to stop through Columbus to check on my mother and her husband.

With predictions growing grim, I sifted through practical and logistical questions before coming to the vocational question: “Do I really think that I am the only person who could bring the gospel that day?!” After that self-examination, I called the Ohio pastor with my regrets. I could be present at Concord.

Our pulpit is scheduled weeks in advance, and the responsibility for that Sunday was my daughter’s. This would likely be the last opportunity for the congregation to hear their pastor’s voice for a while. Was I obligated to preach? I applied the “Dayton principle” to the Concord pulpit: “Do I really think that I am the only one who has a word in this moment?”

Staying consistent, I recognized that Candace could preach and I could pastor, providing the congregation clear and calm directions for our preparation and response to the pending crisis. The sermon that morning was centered on a question the Israelites asked God in the wilderness: “Are you with us or not?”

This was our question also as the pandemic set its sights on New York City. The right word went forth for that question through these days of quarantine, isolation, sickness and death.

What were we going to do in this time of uncertainty to keep the congregation together and provide continued pastoral leadership?

Regarding Sunday morning services, I had resisted livestreaming for many practical, philosophical and theological reasons. Over time, social media has a cruel way of judging live worship, its value and worth, often making much ado about nothing and diminishing significant work with petty likes and snarky comments. I did not want our congregation to be in that.

I also think that there is something very organic about congregational worship, rising out of the collective and communal experiences of people who covenant to be together over time. Worship conveys these experiences and hopes of everyday people. With no offense meant to those who livestream well, for me, organic and messy worship is better experienced in person.

Add to that, we were not ready to pivot technologically to livestreaming. We did not have sufficient equipment or a shared concept of what we wanted to do. A crisis is not a time to run for new platforms. We did not have the time to fully consider our options, and the stores that sold the necessary equipment were now closed. Deliveries were at least three weeks out.

A standard of sustainability

In 2018, we started to talk about what it meant to set a standard of sustainability for every project and program we undertook as a church. This meant assessing our social and economic capacities as well as the environmental impact. Ideas that did not meet these markers sufficiently would not be considered. We had three fundamental questions:

- Do we have the human resources to accomplish the task?

- Do we have the economic resources to support it?

- What is the impact on the environment of the proposed project?

And then as a Black congregation, we ask an additional sustainability question:

- What is the impact on the plight of Black people in this moment in history?

Underrepresented groups are often forced to accept the dominant perspective of assessing all three fundamental categories. We reserve the right to say that our identity as a people is part of our asset base as well -- an asset to be acknowledged, appreciated and leveraged as we anticipate our best possible future.

With these things in mind, we went to work on getting an accurate assessment of our administrative and financial standing.

What questions have guided your discernment in responding to the pandemic?

I started my communication that Sunday morning speaking of our history and our continuing commitment to be present over time to each other and the world. I spoke specifically of our commitment to take care of our working support employees -- that they would be an essential priority for the duration of our shutdown.

The next step was to speak with pastors and officers of the church. We needed to establish a means of care for members and fiscal duty.

A pastor owes it to the leaders of the congregation to communicate with them directly -- to listen to their insights, strategies and fears, and when talking, to be clear and transparent. When the leaders are asked to field questions, our answers would be uniform.

Understanding the technology

I started with teleconference calls with our officers. We would have to start depending on technology more heavily in our routine work. We had just installed a new telephone system that allowed our office telephones to be answered remotely. A box checked, thank God!

Through my experiences on boards and in the seminary classroom, I was acquainted with the essentials of meeting technology, but I am no expert. I worried that the congregation would not be able to make the transition.

My first teleconference call was filled with “takeoff turbulence.” Every plane that ascends experiences some shakiness on the way up. We certainly did. At the end of the call, I asked us to sing together “Blessed Assurance.”

We unmuted our phones and started singing. It was awful. Bad notes, bad pitches, different timings all clashing together, but we made it to the end.

In the spirit of Concord’s conference call, what has gone terribly in your congregation during these months, and what did you learn from it?

As I closed the call, I told them to remember the awkwardness of that experience. Although we were all familiar with that hymn, we were singing now in an unfamiliar and unforgiving medium.

In crisis, it’s important to flatten the hierarchy of communication whenever possible. Although I would not see the congregation regularly, it was important for them to see me, because we are a visual culture and because they could, in seeing me, see the posture and behavior I was modeling.

We all produce the types of members that the people witness in us. I wanted them to see me sheltered in place at home. I wanted them to hear expressions of my faith, to see my best wishes and prayers for their safety and survival, to witness my leaning into God in prayer.

We started with short prerecorded messages and meditations twice weekly, five to 10 minutes each. Production was challenging and time consuming, often frustrating with 25 to 30 takes.

Conveying presence

I have been saying during this crisis that many preachers and their congregations may not survive it. The preacher may not, but pastors will. Now was a time not so much for performed word but for presence, authenticity and hospitality, even in isolation. Especially in crises, people need trusted sources for information about the world they are in and the circumstances they are experiencing.

We have had 20 deaths in our congregation and another 15 deaths within the family members of our congregants. Without question, the cruelest part of this moment is the isolation. Sickness and death happened in profound loneliness at this hour. That is not the natural way we grieve.

How do we convey presence in a time where physical presence is not possible? Our decision was not going to put death on hold. I remember the words of a griot in my life: “When taking something away, always present other possibilities.”

We decided to offer graveside services; streamed funerals and restricted-attendance funerals under the direction of the funeral homes; virtual funerals that we would direct; and memorial services for families who would want to assemble after the present restrictions are lifted. Having multiple options for families to consider is a great comfort.

After three weeks of isolation with only prerecorded messages, we all started feeling the need for gathering. In 1952, the old Concord edifice had burned to the ground, revealing a compelling truth: churches do not burn down; buildings do. In this moment, the building that we closed until further notice would be all that closed.

We began our live online worship gatherings on Easter Sunday. The most powerful moment of these Sunday mornings is seeing other faces. The joy of community is both encouraging and uplifting. Easter was a wonderful day to make that affirmation. Even in death and through death, we are not alone.

This COVID-19 moment is bringing on a new understanding of authority as presence, authenticity and hospitality. The prophet Ezekiel declares, “I sat where they sat” (Ezekiel 3:15 KJV). The form of virtual worship we chose both embodies and models this idea of presence. I am seated in my home, the same as everyone else. It is the power of witness and “withness,” as Len Sweet writes. My authority rises out of a sense of hospitality and solidarity.

We pray and encourage the people to evangelize by sharing the Zoom room with family and friends. We have had people join us from all over the country. A couple in Dallas, Texas, has expressed interest in becoming members.

At the close of worship, we repeat an affirmation that has risen up from our common experience at this time: “I have you. You have me. We have each other. God has us.”

The virtual worship is conveying a new power of fellowship. Typically, at the edifice on any Sunday morning, many congregants linger after worship is over, standing around and catching up. We have found that this ministry does not change in the Zoom gathering.

Every Sunday, we open the Zoom room a little early, and when the worship has concluded, we leave the room open for 15 to 20 minutes. This is joy unspeakable.

Preparing for new ministry

We have transitioned almost every aspect of our existing church program to the virtual platform: midweek Bible study, ministry group and team meetings. New groups are forming because of common needs and challenges brought on by the realities of the pandemic.

We have been reminded that the building itself is not the church. It cannot contain our mission or our responsibility to each other and the claims of the gospel.

COVID-19 has done something that all of the worship services, Bible studies and meetings that churches have had regularly could not do -- it has allowed us to bring our faith into our homes.

Our job at this moment is not to survive the pandemic but to plant new life. I hear people saying, “We can’t wait to get back to normal.” I think the reality is that we will not get back to most of what we had before March 15. Whatever is normal is yet ahead of us, and it will take us some time to arrive at it together.

What I am most clear about is that this moment has opened to us unprecedented opportunity for doing ministry, including new energy from our millennials through the shifts in technology. It allows us to have a church that is not constricted by geography. This is not merely a response to crisis. The virtual church will continue in some form even after we have returned to our physical space.

Concord’s identity as an African American congregation is one of its assets. What does your congregation understand as its core assets, and how are those assets counted in determining priorities and financial sustainability? What does your identity call you to do in light of the current crises?

The ministry will also be challenged to address the residual crises of unemployment, education and social trauma on a scale that we have not witnessed before. Precipitate mental health issues will be overwhelming, and the church has to be positioned to be of assistance in that regard. I believe we are better equipped now than we ever were before to meet those challenges, and the ones that are yet coming with equal resolve.

Staying focused on mission

We have adopted a straightforward mission that we recite together every Sunday: “A community of friends, witnessing for Christ.”

In 1988, the church established a $1 million endowment to support worthy social causes in Brooklyn, but also throughout the world. To date, we have given grants to over 200 organizations and agencies.

Just before the pandemic hit, the church decided that for this one year, the ChristFund would direct its proceeds to alleviating accumulated and long-lasting medical debt. Following the lead from a collective of churches organized by the United Church of Christ and Trinity UCC, our gift of $35,000 was made to the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt, which buys and then forgives oppressive medical debt for pennies on the dollar.

To be honest, there was a little second-guessing after the crisis became real. We could have used that money to shore up our ministry and edifice. But recently, we received news that our gift relieved the debt of over 4,500 families.

What commitments to justice and mercy has your congregation made that are bearing fruit in this season?

We had eradicated all of the available second-market debt in Kings County (Brooklyn) and made a significant contribution to address medical debt in Newark, New Jersey. With our $35,000 gift, $4 million of debt was eliminated.

Jubilee, even in the plague. The people said “Amen!” and looked for the next challenge.

That next challenge did indeed come, an even more daunting and enduring one. What happens when the asset of identity becomes the core of confrontation and disdain in public life?

While Black congregations and communities deal with racism on a daily basis in some form, we could not have predicted that the assault and devaluing of Black lives would grip the center of the public discourse in the middle of a pandemic. The nation was brought to the collective and sobering realization of what Black people experience every day -- we have not finished the aspiration toward “a more perfect union.”

We continue to see the systematic dehumanizing of Black people even in this pandemic. The conscience of America has been struck, and COVID-19 notwithstanding, peoples and churches committed to justice must respond.

I have no doubt that Concord will. We have been “undaunted by any challenge” since the abolition of slavery. It is in our DNA since our founding in 1847, not merely the brick-and-mortar. It is in who we are, not in whether we gather. We declare Jubilee in this plague also. So let us do; so let it be.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- What are the crises through which your congregation has ministered over the years? What did the congregation learn, and do these lessons apply now?

- What questions have guided your discernment in responding to the pandemic?

- In the spirit of Concord’s singing on a conference call, what has gone terribly in your congregation during these months, and what did you learn from it?

- Concord’s identity as an African American congregation is one of its assets. What does your congregation understand as its core assets, and how are those assets counted in determining priorities and financial sustainability? What does your identity call you to do in light of the current crises?

- Concord made a commitment to medical debt relief before the pandemic that has borne witness to Jubilee in the pandemic. What commitments to justice and mercy has your congregation made that are bearing fruit in this season?