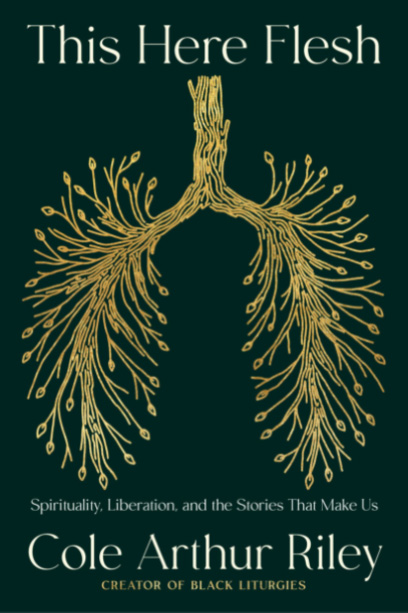

To read Cole Arthur Riley’s “This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation and the Stories That Make Us” is to meet her family and learn how they formed her, in particular her father and grandmother. She tells her story, their story, with beautiful language and lush emotion framed by her contemplative nature and sharp awareness of this moment in time.

Early in “This Here Flesh,” she writes:

My father was born smooth. He glides and sways when he walks, cuts his hands through the air in meaningful arcs when he talks, like he’s in a ballet. I’ve never seen the top of his head because I’ve never seen him look down. He told me from a very young age, Keep your head up, relax those shoulders, look at that skin shine. He told me that Black was beautiful. It seemed to me that he was a man who would never think to apologize for his existence. Some people are born knowing their worth.

At 32, Riley is a New York Times bestselling author, the creator of Black Liturgies, and curator of The Center for Dignity and Contemplation. Her next book — a collection of letters, prayers, liturgies, questions for contemplation and breathing exercises — is in the editing process.

Riley spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne in March after presenting the Jill Raitt Lecture for Duke Divinity School’s Women’s Center. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Could you speak about the importance of the liturgies you’ve written — what those mean to you in the work you’ve done and in the work you continue to do?

Cole Arthur Riley: Liturgy, for me, has been a long journey toward finding spiritual practices that feel authentic to who I am. I wasn’t a very verbal child. I was a very quiet child. I found a lot of comfort in writing from a very early age. I was probably 24 when I first went to a church that had any kind of liturgical, or overtly liturgical, form. And something about the beauty and the writing really connected to me and felt like, if there is a God and if I am going to speak to God, this is how it would happen.

I’m biased, because I’m a liturgist, but I think it’s such a beautiful form for solidarity. What does it mean to stay in words, to stay in a phrase together, even if that phrase doesn’t immediately resonate with you, even if you don’t immediately understand its meaning? To decenter yourself and center the emotions of maybe one or two in the presence of the collective?

I think it’s a beautiful symbol or practice of solidarity and also very restful for me to not always have to manufacture the words on the spot but to just come and accept and receive words without having to try so hard.

F&L: In an interview with Drew Hart, you said that your book is grounded in the Christian tradition you were formed in but your spirituality is more than creed or doctrine. Could you talk about that?

CAR: I’ve definitely known what it is to reduce my spirituality to religion. I’m not one of those “I’m spiritual, not religious” beings. I sometimes feel like my words are misunderstood to be in that camp. I don’t really resonate that much with those words, but what I resonate with is [whether I can] have this larger container for my spiritual life, and religion be one part of that but not to fill the whole cup.

[In the book], I travel into the stories of my father and my grandma. My father is not the least bit religious and would never claim to be Christian or anything like that. My grandma was Christian but endured a lot of abuse that was enabled by the church and so had a really complicated relationship with the Christian church.

As a way to honor their stories and that spirituality, I had to tap into maybe a spirituality that felt more primary in my home growing up. If it wasn’t religion, what form did that spirituality take? I thought a lot about this. I want to put better language to it eventually, but when I was writing the book, I thought about myth.

These are the things, these are the spiritualities of my family — myth, humor, storytelling. Those are the moments where the sacred and the mysterious feel a little more present. So I’ve incorporated myth and story into the book as a form of spirituality.

Now, what could happen if others felt liberated to do likewise? I feel a sense of freedom and not needing to confine my spirituality strictly to doctrines and creeds.

I’m someone who really struggles with belief, and there are people who have a very strong sense of belief. I admire them. I have just never been one of them. It feels authentic to me and my own life to say that I don’t need to be so concerned with answers or this very clear idea of defining my spirituality on this day, but I can just ask questions and allow it to be fluid and drift more into the myth on one day and more into Genesis on another day. I think there’s some degree of freedom in that expansion.

F&L: I’m also mindful in your writing and in your speaking about the toll taken on the bodies of people who live in systems of oppression. I don’t know that people feel very liberated, either in faith spaces or, for people of color, people who are living in poverty, in their bodies.

CAR: If you were raised in a Christian tradition that focuses really heavily on escaping hell someday in the future, it’s very likely, not always, but it’s very likely you are also trained in some level of disembodiment in the present. I think it can train you in a kind of escapism, in escapism from the present with the promise [of the future].

It’s not true hope. I think it’s an illusion of hope, a promise of, “Well, someday you won’t suffer.” And it kind of trains you to forget about the very true physical injustices that you are living and breathing daily. And you just think, “Someday heaven, someday heaven.”

I think it deteriorates our imaginations for good and health and joy and healing in the now. I don’t mean to be so hard on that particular brand of Christianity, but I think it’s a real risk of that kind of theology.

F&L: Another theme is memory and history making. In the Drew Hart interview, you said, “Collective memory is a liberation practice.” We are in this moment where it feels like collective memory is being denied, inverted, perverted, ignored, hidden. Could you talk about the danger in that — when we lose both the personal and the larger version of that?

CAR: I mean, you’re right that this is the moment that we’re in right now. I’m only 32, and I think about this trajectory that we’re on toward trying to limit collective memory and the threat that collective memory is to systems of injustice, systems of oppression in the world. Obviously, if it were not a threat to these systems, they would not care about your AP history classes. Something is happening in those classrooms where collective memory is being curated and preserved.

I think of it as a liberation practice, because I think it’s almost subversive. Because who has gotten the privilege to be the historians up until now, in our country specifically, and in others as well? Whiteness is given the pen and is placed in the role of historian, and we are meant to trust whiteness’s rendering of the past and pass it on in our classrooms.

When we practice collective memory, the role of the historian is shared across a dinner table — between my grandmother and me and her mother and me. This intergenerational, this almost more personal form of memory, I think, can be shaped in resistance to the memory that was delivered to me, these false memories that were delivered to me in my classrooms growing up.

We could subvert the white historian by just electing a few really smart Black historians. I think the resistance is, “No, we’re not going to do history the way you do history. We’re going to practice memory.”

It will contain history, but it’s also going to contain stories and myths and traditions and rituals, and it’s going to be just as meaningful at a dinner table as it is from an academic. There’s meaning in both forms of exchange, not just people who have access to the academy.

There’s a little bit of liberation there as well. I could talk about this for a while, but I think I want to write a book on memory. The role of story in terms of understanding myself — it helps me understand what I’m worth as well, and it reshapes the things that I’m hoping for.

People tend in Q&As to ask me about hope. And the thing that feels most true to me in this season is that my hope is actually found in looking back in memory and kind of bridging that space. Because once I remember rightly, or as rightly as I can with the people that I trust, I feel like my appetite for good and health and well-being in the world is refined.