Tonya Rice didn’t hesitate.

She slipped an index finger beneath her upper lip, pulling it back to reveal a row of misshapen, decayed teeth. A moment later, she let go, and the evidence of past neglect was hidden again, outshone by her soft blue eyes and a freckled, peaches-and-cream complexion.

“I can show you this now,” the 29-year-old said, “because I’m not embarrassed anymore.”

After nearly six months at the transitional program offered by The Next Door in Nashville, Tenn., Rice discovered what many other addicts have yet to. It’s OK for her to be honest about ugly truths -- even if they include a crack and cocaine habit that bankrupted her relationships, led to the loss of her children and landed her in prison. Acceptance, grace and forgiveness can be more than just platitudes. And mutual respect goes a long, long way.

“I know one day I’ll walk out of here with a beautiful smile,” she said. A local dentist has offered to repair the physical damage.

Look in those eyes, however, and it’s clear the beauty of that smile will come from more than just her teeth.

Crossing the threshold

From the outside, The Next Door is a nondescript, unmarked downtown building. Beyond the surface, however, transformations are taking place for the women in crisis who come for help.

At this residential program focusing on women leaving prison, there are no must-be-mentioned success stories, no standout stars. There’s also no us-versus-them mentality. There is only a group of women -- staff and residents -- jointly dependent on a divine hand for intervention, guidance and wisdom on a minute-to-minute basis.

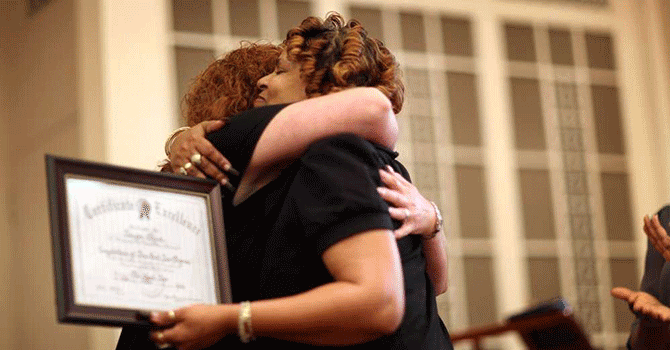

On a warm November Sunday, the community has gathered in a small chapel nearby. Dressed in their best, anticipation in the air, they wait for the “transition” ceremony to start. And they watch as four women, including Rice, stand on their own.

It’s a graduation day, and one by one, each of the four approaches the microphone before the crowd of about 150, chokes back tears, steadies her hands and musters the courage to share stories of struggle, defeat, loss and victory. Seated before them are staff, volunteers and other residents as well as also family members and friends. They look out into faces of those they don’t want to let down again.

Disappointment has dotted these lives, a constant among the 500 women who have crossed the threshold of The Next Door since May 2004. They arrive from prisons, county jails, violent relationships and less-than-legal work on the streets, carrying with them histories of substance abuse and hope for a better future.

Many are like Sandra McIntyre, whose quarter-century dance with drug addiction began when, as an all-star teen basketball player, she was hit by a drunk driver and lost her ability to play. The women at The Next Door brought her true community in ways she’d never known.

“I don’t have to hide anything,” she said from the front of the room.

And the standing ovation began.

‘Trust equals love, and that’s huge’

Across Tennessee, according to the state’s Department of Correction, the average recidivism rate for all offenders -- the number who will typically relapse after having served time in prison -- is 42 percent within three years. At The Next Door, it’s 10 percent for those who complete the six-month program and 21 percent for those who stay just 90 days. The program is so successful that it has been recognized by the White House, the National Criminal Justice Association and the Office of National Drug Control Policy, among others.

Some chalk it up to the holistic combination of compassionate care, clinical services, structure, grace, community and affordable housing. Some say it’s in the spiritual emphasis. Still others say it’s in the example the staff and volunteers set. But what truly sets it apart is the decidedly Christian -- and unusual -- willingness to hand over trust, acceptance and mercy to those who fully understand that they’ve thrown away those opportunities in the past. From the program’s outset, the decision was made that trust would be given rather than earned.

“Coming from a place where I had been not trusted, where I had been labeled, that gave me hope,” said Ramie Siler, a former resident who is now a case manager. “It was the first time I felt like the world didn’t look down on me. It made me feel safe, and gave me confirmation that I could make the changes I needed to.”

It wasn’t easy; it rarely is. Of the many that have been accepted, just about 100 have made it through to graduation. Linda Leathers, The Next Door’s executive director, admits that it’s all about grace, but that grace is not cheap.

“It’s the easiest thing in the world to go back to your old ways,” she said. “This is a new way of living. We’re asking these women to be responsible for themselves. It’s not always rah-rah-rah.”

Experience has taught the staff that they can’t live the lives of the residents for them. They can’t want recovery more than the addicts themselves. This knowledge led to healthy boundaries, but also a clear view of what was really needed.

The downtown Nashville residential building next door to the First Baptist Church houses up to 44 women. The program also offers regular meetings (open to those in the program and beyond it); prayer partners with women in the outside world; chores; employment assistance; life-skills training; help with family reunification; a separate, gated community for roughly 20 women who have graduated; individual and group counseling and more. To teach responsibility, participants are expected to hold a job and pay $125 a week; they’re also encouraged to save.

But relapses happen. Setbacks occur. And when they do, the women involved aren’t kicked out of the program. More services are placed around them instead. The enduring compassion stems from the understanding that addiction is often related to past trauma such as emotional, physical or sexual abuse.

“Essentially, these women may be trying to deal with things that happened 20 years ago,” said Cindy Sneed, a counselor and mental health services provider who is the organization’s chief clinical officer.

Working through that effectively includes core values such as wholeness, hope, community, respect, encouragement and faith. And, again, trust, which Sneed considers key to bringing the rest about.

“Now that means we’re going to be disappointed sometimes,” Sneed said. “We’re going to be hurt. But that’s exactly what God does for us. If I don’t have to earn his trust, then they shouldn’t have to earn mine. I know that’s a little backwards, and some alcohol or drug treatment centers would say we’re crazy. But as a faith-based organization, it’s a critical point to our success. For these women, trust equals love, and that’s huge.”

Miracles by the day

Throughout the graduation, the women talks about daily dependence on God -- it’s a charge and a confession. One woman urges others to remember John 15, to remain connected to the vine in hopes of bearing fruit.

But the message is more than words. For the women of the program, it has been a persistent example. Many faith-based organizations incorporate prayer and biblical counsel. But The Next Door takes it to another level. The joke is that miracles happen here every day -- and not just in the lives of the residents. There are the down-to-the-detail supplies that arrive at just the right moment -- including shoes in exactly the right style, color and size -- and $165,000 needed to renovate the building’s top floor. The latter was in hand within 24 hours.

“What can I say? We’re living the dream,” Leathers said.

It’s a dream that dates back to the spring of 2002, when Leathers was a staff member at First Baptist Church. A small troupe calling themselves the “Wild Group of Praying Women” began asking God what should be done with the church’s empty building. It was up for rent, but Leathers and others felt a burden to use it for something good. Something good for women in particular.

“We were open, and we were sensitive to God’s leadership,” Leathers says. “But we were clueless.” They conducted a community needs assessment, visiting different agencies and asking where the disparities were. They weeded out ideas such as low-income child care and refugee assistance. The first four prayer warriors grew to a group of 12, and then to more than 100.

“And what kept coming to the forefront was the gap in services for women coming out of crisis situations, addictions, mental health disorders, poverty and, uniquely, coming out of incarceration,” she said. “Now, in 2002, I didn’t really know what incarceration meant. So we went to the jail. And we were told, ‘Ladies, this is tough work. But if you can make an impact in one woman’s life, you’ll change a generation.’”

Creating a different paradigm

The stories of success continue to foster hope. In addition to its Nashville program, The Next Door is expanding to Knoxville and Chattanooga. It’s not because “bigger is better,” Leathers explains, “but because the need is so vast.” Staff has been hired, community connections have been made and the search for the right facilities is underway, but Leathers said the biggest challenge is how to recreate the grace- and humility-filled culture.

Jim Cosby, assistant commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Correction, said he wishes The Next Door could help even more women. In 2008, Tennessee prisons released more than 2,100 females. Many of them were headed back to their home communities -- and, sadly, their previous lives.

Being able to enter a place where they’re immediately trusted, however, “is a different paradigm for the offender,” he said. “I believe it presents a new perspective, one that’s well received.”

And one that come to engage the larger community, as well. Andrea Overby, The Next Door’s founding board chair and ongoing volunteer, has uncovered numerous misconceptions in her days with the organization. She also has had to overcome many of her own.

“Some might think, ‘Why should we try to help these people? They’ve been in jail. They’ve made their choices,’” she said. “What I want to say is, they’ve done their time. And if they have a real determination to change, that’s why we’re here.”

First Baptist Church still rents the building to The Next Door for $1, but the organization has grown beyond the single congregation to become a community endeavor. The individual and church gifts that make up more than a quarter of the organization’s $1.2 million annual budget involve some 300 people and 50 congregations; the rest of the funding comes mostly from foundations, corporations and government grants. Volunteers range from teens to the white-haired seniors that add a constant presence of grandmotherly love, and though the program is not evangelistic in nature, the opportunity is always there. Hope and its source are ever-present, and community is available to all who would receive it.

“It’s so refreshing to see these women -- who come in here and can’t even look you in the face, wearing sweats and a T-shirt that has a prison number on it -- become a part of the process, a part of the community, a part of something bigger than themselves,” Leathers said.

Just upstairs from where she speaks, Ramie Siler works away in her office. Now in charge of Lifetime Recovery Management, which helps graduates and others reconnect on a regular basis, she said recovery remains an ongoing process, and it always will be. It was just a few years ago that she was incarcerated herself, but The Next Door has put tools in her hand she now knows how to use.

“This place lets you know that your past does not define you,” she said. “The Next Door literally is the next door. This is about the next phase of your life, the beginning of your journey.”

It’s the beginning of Tonya Rice’s journey, too. As she stood during that recent graduation, sun streamed through the windows, highlighting a life transformed in body, soul and spirit.

“I do believe in Tonya,” she said.

And then she smiled.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider:

- How would you rate the degree to which members of your community feel they can be honest about ugly truths and do not have to hide their true selves? Does this kind of comfort level help create a thriving community?

- How does a leader foster an atmosphere of assumed acceptance and trust within his or her community?

- How is trust in another human being a sign of love for them? Why do you think trust is such a redemptive a force in the lives of the women at The Next Door?

- In what ways has God trusted you? How has this trust proved redemptive in your own life?

- What theological understanding lies behind The Next Door’s response to relapses and setbacks? How do you as a leader tend to respond when those in your community disappoint you?

Teaching Tools

Lessons learned at The Next Door

One of the most important components of The Next Door’s thriving sense of community is mutual respect. For staff members, that means they learn as much as they teach. Here’s what some staff members say about how they’ve been affected by the residents of the transitional program for women in crisis:

“I know that God truly is in the transformation business. I see it all the time. These women are walking examples of grace to me. It’s a subtle thing, but I fully realize that I’m no better than they are. I just haven’t experienced some of the things that they have…. I hope that I treat the women here just like I’d treat our greatest donor.”

Linda Leathers, CEO

“I’m still surprised every day. I’ve heard some of the most horrific stories. And these women have trusted me with them. Just when you think you’ve heard the worst part of humanity, you hear another story that makes the last one pale in comparison. It’s amazing that these women have survived the things that they have, and that they’re just still showing up every day. That’s huge. I’m impressed by the depth of courage that these women have. Just to imagine what they’ve gone through to get to this point, to even begin to try to heal, is spectacular. Their resilience is amazing.”

Cindy Sneed, chief clinical officer

“I’ve realized that I had a lot of misconceptions about this population. I came here from a corporate background, and what I had visualized in my mind was that every woman who had been in jail or prison was mean, scary and couldn’t be trusted. But I’ve realized I was totally wrong.... I can’t think that any one of the women here would ever take something from me, harm me or do something to disappoint any one of us intentionally.”

Ginger Gaines, operations director

“[The women] have taught me to appreciate the blessings that come as a result of their determination to change their lives. The successes and achievements of the residents turn into blessings for me as well, and it makes me feel privileged to be even a small part of the process. Things that were formerly problems for me now seem insignificant compared to the obstacles these women must overcome.”

Andrea Overby, founding board chair and volunteer

“I’ve learned how to work with all types of people, to not be judgmental, and to be grateful for the life I have as well as the opportunity to be a part of theirs.”

Mary Rufener, volunteer coordinator

“The women teach me humility. They keep me grounded, and they teach me to be grateful.”

Ramie Siler, case manager and former resident