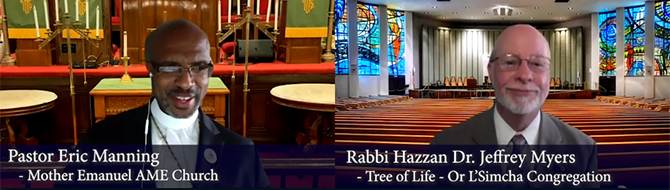

Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers and the Rev. Eric Manning have an uncommon bond, born out of unspeakable tragedy. Both faith leaders minister to congregations wounded by mass gun violence.

Myers had been at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life congregation “just a pinch over a year” when a gunman opened fire during Sabbath services, killing 11 and injuring six, Oct. 27, 2018.

Manning arrived at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston a year after the massacre that killed nine church members, including the senior pastor, in 2015.

As the Tree of Life community prepared to mark the second anniversary of the Pittsburgh shooting, both leaders spoke with writer Stephanie Hunt about what they have learned from their experiences and about their friendship. The following is an edited transcript.

Stephanie Hunt: Rev. Manning has talked about how his role at Mother Emanuel has entailed being in the public eye more than he might be otherwise. Being a rabbi and a congregation leader is always a public position, but you’re now, in a way, rabbi to the nation, which is what seems to happen in the aftermath of something like this. How have you balanced that?

Jeffrey Myers: There are really three pieces to balance. There are my responsibilities to my congregation. There are the continued asks from those outside my congregation. But then I also have my family.

Balancing all of those is challenging. There are no training classes, no books to read on how to do it. It’s gut instinct. I try to surround myself with people who can give the right forms of advice, including media professionals who help filter and organize, help determine the best ways to share what the message might be. Media requests can be overwhelming, and there’s only so long your battery can run before it just gives out.

My priority is my congregation. Then when I can, I fit in the things that are outside the purview of immediately focusing on my congregants and their needs. In the end, most likely my family suffers, because time with family is often the only time left to take from.

SH: Along those lines, Rev. Manning has become one of those offering helpful advice. He reached out to you via email after the shootings, but my guess is other ministers did the same. What was it about his email that made you respond?

JM: I remember sitting down on my living room sofa, I think it was that Tuesday after the massacre was that previous Sabbath [Saturday]. I hadn’t really looked at any media or the news; I didn’t need to, because I was the news. I was living it. I just sat with my family and happened to pick up my phone, open it up and look at my emails -- which blew me away. Thousands upon thousands of emails.

You know when you scroll through email with your finger? Well, I was just scrolling, and like the moment when the one-armed bandit in the casino is rolling the numbers, then it stops and rests somewhere -- well, eventually my finger stopped, and it rested right on his email, like it was the finger of God. Right?

I saw the email header, which mentioned Charleston, and because I knew of the massacre there, I opened it. Rev. Manning had written a beautiful note and in essence said he wanted to come into town. But you can’t know how many hundreds of people were coming to town or asking to come to town. So my initial response was, “I’ve got so many people, I can’t figure out where to fit this in.” But he was insistent.

So I agreed and found time Friday morning, before the last of the funerals on Friday afternoon. Somewhere there was just some push. Maybe God was saying, “Go meet with him. Go. Go.”

SH: Rev. Manning, what compelled you to reach out to him?

Eric Manning: When I came to Mother Emanuel, I realized that there were not a lot of people I could talk to about what I was processing, what I was dealing with, how to respond to media -- all these things that no one prepares you for.

I think we at Mother Emanuel had not necessarily gotten it all correct right off the bat, so I wanted to share what we had learned. I just reached out to let them know that we’re praying for them, that we’re here as a resource if they need it, and that was it. Did I ever expect a response? No. But I did know early on that I was going to make my way to Pittsburgh.

SH: So in addition to hoping to support Rabbi Myers, it was also in part your need for a comrade who was going through the same thing as well?

EM: I wanted to be a support for Rabbi, because when I came to serve Mother Emanuel, there weren’t that many people I could talk to about how to deal with the congregation, about all the things that I’ve prayed through and learned as I took the congregation through the trials.

I didn’t want the rabbi to have to go through all the growing pains, so to speak, that I went through. I wanted to be a ministry of presence, to be there to let them know that we’re with them.

SH: I’d love to hear about the ecumenical aspect of your friendship. Were there barriers you had to cross?

JM: As a rabbi, I had no other synagogue to turn to, because this had never happened. Thank God it’s a small club when it comes to clergy, but alas, there is a club.

Though we come from different points of view, far more unites us than separates us. The things that make us different aren’t barriers; they’re just places where we can learn from each other.

EM: Exactly. Rabbi has heard me say this a number of times -- if I can meet people in Genesis chapter 1 and chapter 2, we’re rock solid. From the ecumenical perspective and from a Jewish faith perspective, we can meet in sacred text in the book of Psalms. That’s the beauty of it.

When you have a desire to meet people on the basis of our common humanity, you do the work to ensure that you are not going to superimpose your faith tradition on anyone; you’re just there as a fellow human.

When there are these hateful acts, it’s up to us who are survivors, as Rabbi is, and those who are serving congregations where mass trauma and tragedies have taken place, to do the work, to just say, “Let me first be there” and then say, “We will get through this together.”

I don’t think our faith traditions have ever been a barrier. It’s a beautiful thing when all of God’s children can come together to comfort, inspire and help each other through the trying seasons of our lives.

JM: From a different point, I was talking with Wasi Mohamed, whom I think you met when you were in town?

EM: Yes.

JM: He was the former executive director of the Islamic Center [of Pittsburgh]. We’d spoken about how the sons of Abraham were able to come together. Because as Jews and Muslims, we’re both children of Abraham. We have common parentage, and we are called to be our brother’s keeper. It’s imperative.

SH: Rabbi, you mentioned areas where you’ve been able to learn from each other. I was hoping you both might speak more about that. What are things that you’ve learned from your relationship with Rev. Manning and others as a result of this, in terms of leading a congregation and in your own spiritual life?

JM: That this strength of faith that runs through us is a powerful force to be reckoned with. It’s the closest thing to what the Star Wars pantheon calls “the Force.” This force that flows through us is an indescribable source of constant support. I’ve found that to be so powerful, whether when I’m in Rev. Manning’s presence or in Wasi Mohamed’s presence.

It’s almost like some sort of nuclear reactor, an energy source, constantly humming, constantly going. The challenge as a faith leader is to find how I can help reassure and instill that feeling in my own congregants, particularly ones whose faith has either lessened or those who have totally lost their faith because of what happened to us.

There’s nothing that says a Jewish clergyperson can’t help those of a different faith find ways to restore their own faith. The faith that flows through all of us is the same, and I think that’s an incredible thing to realize.

SH: Rev. Manning, care to add anything about what you have learned?

EM: I’m reminded that though we serve very different congregations, though we may have different faith traditions, we can find ourselves battling the same issues. I’m reminded, too, of the importance of sympathy, empathy and compassion.

I do think it’s interesting, though -- and this happened at the supermarket just yesterday -- someone will approach me to say, “Well, the way your church responded was so inspiring.” I understand that response, but no one talks about the hatred that led to the event. We focus on the tail end.

From my perspective, that’s very concerning. We don’t want to deal with the hate. Rabbi, I know, doesn’t use the word “hate” -- instead he says “H-word.” But I think that’s something we need to continue to unify and rally around.

In Charleston, I partner with the Jewish community in [an initiative called] Stamp Out Hate South Carolina, because it’s important, and I think we need to focus on that.

SH: How often do you interact, and is it casual, like sending each other a text, or are there orchestrated meetings?

EM: Everything is very choreographed; I don’t call Rabbi unless I need something. No, I’m kidding. It’s very casual.

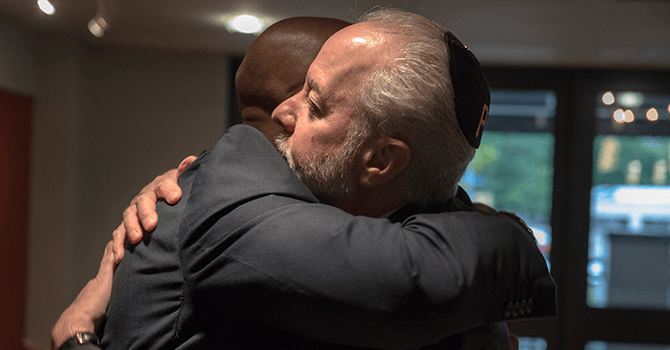

JM: It’s like two friends who pick up the phone and talk. And it’s reassuring to know that while sometimes two, three or four weeks might go by when we haven’t spoken, that doesn’t mean we’re not on each other’s minds. It’s this continued chronology that flows.

SH: How would you say your congregations are doing today? Are there patterns that you can recognize, a shared sense of “here’s what to expect”?

JM: We’re the younger sibling, so to speak, so watching and eagerly following the goings-on at Mother Emanuel allows us to grow from their experiences in terms of things to look for and things to expect, things to watch for, challenges that are yet to come. They’ve got a more vast playbook, which is helpful.

For example, they have already started a campaign for a memorial. That’s interesting for us to observe as our victims’ families are beginning to meet and talk about the same thing. We’ve watched Mother Emanuel start a campaign to work on their building, and we’re on the cusp of doing that as well.

We’re learning things that might help us along the way, help us heal and also maybe help us avoid a mistake. We’re able to say, “OK, why would this not work for us?”

EM: To Rabbi’s point, there may have been things that we didn’t get right, which I shared very candidly when I first visited with them. I was called to Mother Emanuel a year after the shootings, and there were things that had been done that if I was there, well, we may have made different choices. I think that was helpful to discuss. Rabbi, from what I understand, you all are getting ready for the trial here soon.

JM: Actually, it was supposed to originally be starting soon. Due to the pandemic, it’s been deferred to, I believe now, sometime the early part of next year.

EM: Unfortunately, we went through the same thing -- delays after delays after delays. Then when it finally started, I remember the anxiety that was there. There will be opportunities for me to share with Rabbi about getting through the trial, from a post-five years perspective.

Five years later, you have people who are finally ready to trust you to talk about how they feel. You have to wait for others to be ready to talk, for them to trust that you do care, and trust that, though you can’t go back and change things, you’re willing to listen and to share and be there.

It’s like anything else -- it takes time. Last year, I got an opportunity to go to 16th Street Baptist Church [in Birmingham] and interact with some of the survivors. And much to my surprise, they are still trying to process it.

SH: Rabbi, is there something that the two of you are working on that you want to drop any hints on?

JM: Well, I can mention one thing. In addition to being an ordained rabbi, I’m also an ordained cantor -- the trained musical pastor who leads the congregation in worship. Our professional organization is called the Cantors Assembly, an international organization of over 700 ordained cantors who serve congregations throughout the world.

We’re getting ready to launch a wonderful video project created with roughly a hundred voices of both cantors and Black church music ministers based on the piece “Total Praise” by Richard Smallwood. We’re releasing that as a message to the world about the power of music.

Later today, Pastor Manning and I are going to be meeting once again on Zoom to record a short conversation about this project, as well as the ancient history that goes back between the Jewish and Black communities.

SH: Is there anything else that you would like to share about the power of your relationship, the power of healing, what it means to have a ministerial friend from a different faith tradition throughout this process?

EM: I would say never allow various traditions, faith traditions, to prohibit you from getting to know people. We had a memorial last year for the attack that took place in New Zealand, and I went to our local imam, who is another great friend, and said, “Today, I am Muslim.”

Now, that may make some of my seminary colleagues cringe, but from an ecumenical perspective, I have embraced, as Rabbi said, that as children of Abraham, we must meet in places that we can draw strength from. At the end of the day, we draw strength and encouragement to continue on this journey that God has placed us in.

JM: I was just thinking that horror thrust the two of us together, but that’s not what kept us together. There’s a brotherhood -- not in a sexist sense, but in terms of a connection that continues beyond being sons of Abraham. We’re all children of Adam and Eve, and there are too many people on this planet who have forgotten that.

The vast majority of humanity, I still believe, is made up of good, decent people. The balance is just off. We have too much reporting on all the bad, all the evil, and it makes people think that humanity is headed in the wrong direction.

I think, respectfully, the media needs to do a midcourse correction and improve that balance. If we continually read bad news, how can we not be depressed -- which makes our job as clergy even harder.

We must seek out these powerfully good, important, wonderful things that are happening throughout the world. We need to give people uplift, particularly during a pandemic. As clergy, we can’t do that all by ourselves.

How will Tree of Life mark the second anniversary of the shooting?

How will Tree of Life mark the second anniversary of the shooting?

Rabbi Jeffrey Myers: We have a commemoration committee working with the Pittsburgh version of a resiliency center -- I think there was a similar center in Charleston. We call it the 10.27 Healing Partnership, and they are helping with engagement with the victims’ families -- representatives from each of the three congregations that were in our building at the time of the shooting -- to craft what the second-year commemoration will look like.

The focus will be community service, to whatever degree we can do that during a pandemic. Judaism always finds the study of texts important, so there’ll be Bible study as part of that.

Also, from a Jewish perspective, when we observe the annual date of death of someone, the Jewish faith follows the lunar calendar, not the solar calendar, so that means the dates don’t coincide. This year, the date that we observe to commemorate their deaths on the Jewish calendar is Nov. 5.

We’ll continue to also observe Oct. 27, because that’s the date that the general public will always remember. In essence, we observe two dates. One is the grander, more public commemoration on the 27th, and the other, a more private commemoration.