My brother Silas recently texted me a screenshot of a Wikipedia page about our ancestor, his namesake: “Did you know this?”

“Talbot was not only a slaveholder,” it read, “but from 1783 onwards was the partial owner of two slave ships. … Both vessels transported slaves from the Guinea region to Charleston.”

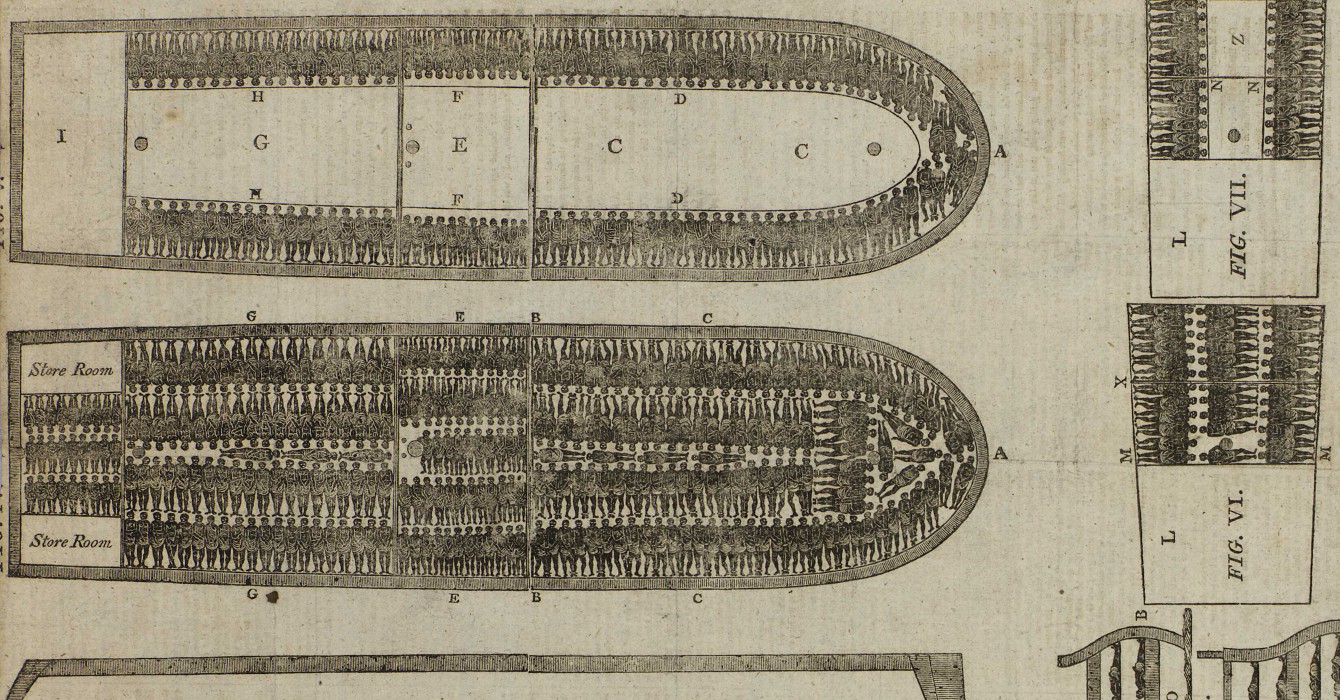

It goes on to say that on a 1786 voyage of one of these ships, the Industry, about half of the 180 kidnapped people died before the ship landed in Charleston.

I took a sharp breath and closed my eyes, shaking my head, exhaling.

We were raised with this man’s story — a coffee-table book about him in the living room, a painting of the U.S. Navy ship he captained on the wall, a replica proudly displayed in my grandparents’ cabin. I remember being taken as a child to visit the USS Constitution in Boston Harbor and my brother being asked whether he wanted to sit on his great-great-great-great-great-grandfather’s bed. There was never a mention of slavery.

I learned about racial oppression in college, but it was all too easy to pretend that these were abstract, intellectual histories, disconnected from me or my white family. In the following years, working in the youth climate justice movement, it would take Black and Indigenous peers and elders repeatedly asking me, “Who are your people?” for me to turn my attention back to these family mythologies.

A first step was opening that long-dusty coffee-table book. Right there, in the first few pages: “Primus was the first of many slaves that Talbot would own during his career. Indeed, whenever he lived where slavery was legal Talbot owned a slave.” It was the first evidence I found of my own family’s participation in enslavement.

That discovery set me on a path, which continues to today, of listening for what is mine to do in response to this devastating history. Not long after, some internet searching revealed Talbot’s investments in slave ships. But I had not known this particular story, of this unfathomable loss of life between Guinea and Charleston, until now.

My phone dinged. I opened my eyes to another text message from Silas, a link to an academic journal of early American history. In it, our ancestor’s own words about this very incident, transcribed from a handwritten letter to a business partner: “Perhaps, Sir, there never was a Voyage that turned out more compleatly unfortunate to any Mortal than that performed by the Industry as it regarded myself. … I now declare that I never received a shilling. … I lost the whol[e] of that Property.”

“Are you still breathing?” asks Alexis Pauline Gumbs in the opening of “Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons From Marine Mammals.”

“I am talking about the middle passage and everyone who drowned and everyone who continued breathing. … This is an offering towards our evolution, towards the possibility that instead of continuing the trajectory of slavery, entrapment, separation, and domination and making our atmosphere unbreathable, we might instead practice another way to breathe.”

Sometimes, when I encounter the brutal truths of the harms my ancestors caused, I forget to breathe. Air catches in my throat. I become lightheaded. Then comes the instinct to do anything else but sit with the truth: Isn’t the laundry almost done? Wasn’t I about to get a snack? What was that crucial email I have to respond to? How can I return my heart rate, my breathing, my life, to normal?

This time, with Gumbs’ words in my mind, I decided to keep breathing. I found a candle and lit it, stomach churning. With the light to anchor me, I went to the darkness, to the fear, to the wet and creaking hold. Ancestor Silas deemed those who took their last breaths here less than mortal. So I attempted to connect my breath with theirs.

Ninety deep breaths, in and out, in and out, one for each of those lives lost in the “unbreathable circumstances” of my ancestor’s ship. One for each man, woman and child whose capture, separation from family and homeland, sickness and, for many, death at sea Talbot considered less “compleatly unfortunate” than his own loss of a financial investment.

As I’ve navigated these treacherous waters of my family history, I’ve come to understand this work of reckoning as a spiritual practice. Breath has been a starting place, a practice for unlearning the numbness that whiteness has taught me, for relearning how to feel. Through breath, I am building over time the capacity to let in the depth of the trauma my people have caused. As I do, I am learning to see that the pain of ongoing racial harm today is not separate from my ancestor’s choices some 200 years ago.

In his work with the Grassroots Reparations Campaign, my friend and teacher David Ragland invites members of faith-based communities to pledge to be reparationists. In the campaign’s words, “Reparationists engage in a spiritual journey to heal from white supremacy in all of its external and internal manifestations while working toward full reparations and abolition-democracy.”

I’m grateful for the opportunity I had to study deeply with Ragland while at Harvard Divinity School, where I advocated for him to be hired to offer his course “Reparations as a Spiritual Practice.” The class was oversubscribed, a demonstration of the desire divinity students have to integrate their spiritual questions with the moral and political imperative of reparations. More than anything, this course deepened my conviction that the call for reparations for slavery is not separate from my own need to heal from the spiritual injury that has been handed down through my lineage.

At the same time, reparations are necessarily material. While my ancestor lost money on the Industry’s 1786 kidnapping expedition to West Africa, he still died a rich man, having owned ships and businesses, land and real estate. No part of his economic gains can be considered fully separate from the spoils of slavery. Whether trading in tobacco, sugar, cotton, rum, land or human beings, every part of his engagement the 18th- and 19th-century U.S. economy was bolstered by stolen lives and labor.

While many in my family consider themselves “not rich, just upper-middle-class” today, the trappings of this 19th-century wealth are still visible: property and land ownership, heirloom antiques and oil paintings, trunks of old business records, Ivy League degrees. When I was 22 years old, I learned that $600,000 had been invested for me — which is one way that I have seen this.

In the 10 years that have followed, I have divested these funds from the stock market and redistributed them in support of Black- and Indigenous-led organizing, healing and land projects, in recognition of my family’s history. While individual acts of divestment and resource return are not reparations on the systemic and governmental scale that is needed, they can be part of building a movement that can yield larger transformation.

And for the many who do not have family wealth, there are myriad other ways to be part of building this “culture of reparations.” From refusing to invest retirement funds in extractive industries that profit from incarceration and war, to organizing for the removal of statues and the renaming of public places that honor enslavers, to defending the teaching of these histories in public schools, this work of repair is multifaceted and lifelong, and it requires all of us.

The last section of the Reparationist Pledge of Accountability reads, in part: “I pledge to take this message to my family, friends and community with love rather than through guilt or shaming.”

To that end, I invite you to join me, in breathing and surrendering, in listening and organizing, out of love for all people, knowing that those who have gone before leave unfinished work for each of us to pick up. The next chapters of our family stories are yet to be written.

That discovery set me on a path, which continues to today, of listening for what is mine to do in response to this devastating history.